While most people are familiar with the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, with figures like Cicero, Caesar, and Augustus, few people know of the existence of the Roman Kingdom. For over two centuries, from the legendary foundation of Rome (c. 753 BC) to the establishment of the Roman Republic (c. 509 BC), Rome was ruled by kings. This period is shrouded in mystery, however, because there are few reliable sources. Our main source is Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita, but even his historical accuracy is questionable, especially regarding Rome’s earliest history.

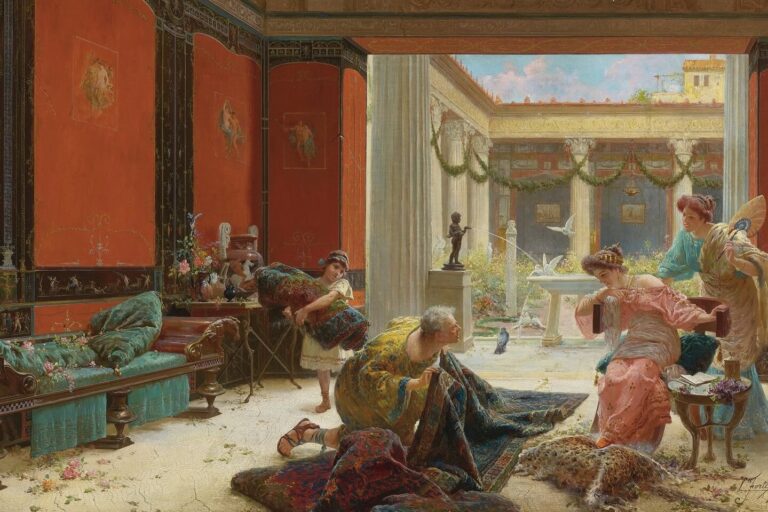

(Wikimedia Commons)

“Events before the city was founded or planned, which have been handed down more as pleasing poetic fictions than as reliable records or historical events, I intend neither to affirm nor to refute. To antiquity we grant the indulgence of making the origins of cities more impressive by commingling the human with the divine.”

Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, Praefatio 7 (trans. T.J. Luce)

1. Romulus

(Wikimedia Commons)

Though most people are acquainted with the myth of Romulus and Remus, few people know much about Romulus as the first king of Rome. After killing his brother and founding the city named after himself, Romulus aimed at organising and expanding the city. His first acts were to establish political bodies like the Roman Senate, to raise an army, and to increase the population by granting asylum to fugitives from the surrounding areas. However, most of these asylum seekers were men, so Rome was in dire need of women to increase its population. Romulus therefore devised a plan: they organised festivals and games, invited the Sabines, a neighbouring people, and then at a given signal carried off the women.

This act of trickery and deceit, however, greatly angered the Sabines, who then took up arms and advanced towards Rome under the command of their king Tatius. It might have been the end of Rome, if it was not for the Sabine women intervening between their fathers and brothers on the one side and their husbands on the other. Thus, the Romans and Sabines came to terms, made peace, and ruled together for many years under the joint leadership of Romulus and Tatius.

2. Numa Pompilius

(Wikimedia Commons)

The second king of Rome was Numa Pompilius, a man of Sabine origin. It is clear that he was the opposite of Romulus in almost every way. Romulus was a king of war, while Numa was a king of peace. More than anything else, Numa wanted peace. In order to temper the warmongering of the Romans, he instilled fear of the gods in the heart of every Roman. His reputation as a pious man helped him in this matter, for he had devoted his life to religious contemplation, and he was even said to converse with the gods.

Numa established the most important religious institutions that would stay in place for countless centuries, such as the Roman calendar, the Vestal Virgins, and the office of pontifex maximus. Exemplary for his reign was the temple of Janus he built, the doors of which were shut in peacetime and opened in wartime. During the whole of Numa’s reign, the doors remained shut.

3. Tullus Hostilius

(Wikimedia Commons)

The third king of Rome was Tullus Hostilius. He was the opposite of Numa, like Numa was the opposite of Romulus. Being even more warlike than Romulus, Tullus believed that Numa’s peacekeeping and pious policy had kept Rome weak, feeble, and unprepared for hostile attacks. So instead of seeking peace and stability, Tullus actively looked around to find a pretext for war. Eventually, he found an enemy in the neighbouring Albans, whose settlement was situated on the hills of Alba Longa.

To prevent unnecessary bloodshed, they agreed upon single combat. Each side held three brothers, triplets, who were chosen to represent their people: the Roman Horatii and the Alban Curiatii. In battle, two of the Horatii brothers were killed in quick succession, so that only Publius Horatius remained. Outnumbered by the three Curiatii, he fled to a distant spot so that they would split up in their pursuit. Thus, Publius was able to face the Curiatii one by one, eventually killing them in single combat. So it was decided that the Romans ruled over Alba Longa. When the Albans betrayed the Romans in a later war with the Etruscans, Tullus razed Alba Longa to the ground, and moved its people to Rome. He gave them Roman citizenship and incorporated their leaders into the Roman Senate. To accomodate for the increased amount of senators, he then ordered the building of the Curia Hostilia in the Forum Romanum and designated it as the new Senate House.

4. Ancus Marcius

(Wikimedia Commons)

The fourth king of Rome was Ancus Marcius, a son in law of Tullus Hostilius and the grandson of Numa Pompilus. He attempted to follow in the footsteps of his grandfather, but he did so with far less success. He introduced rituals to prescribe how the Romans should declare war upon their enemies, though it has been argued that this merely gave the Romans the appearance of legitimacy. When Ancus Marcius was in power, though, the Romans were for once not the aggressors.

Thinking that Ancus Marcius would piously pursuit peace like Numa, the Latin League opened an attack on Rome. Ancus Marcius declared war to the Latin people and sacked many of their cities, moving their inhabitants to Rome. After putting down these uprisings, Ancus Marcius took upon himself the task of expanding Rome’s territory. He incorporated the Janiculum Hill into Rome, and, more significantly, founded the port of Ostia south of Rome. It initially functioned as a naval base, and it was not until the 2nd century BC that it became a commercial port as well.

5. Lucius Tarquinius Priscus

(Wikimedia Commons)

The fifth king of Rome was Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, a man of Etruscan descent. He was a successful ruler, known for his political reforms, military success, and his innovative construction programs. As for political reforms, his first act was to expand the senate to a total number of 300. Because the new senators thanked their position to Tarquin, they supported him in everything he did, thus strengthening his position as a king. Concerning his military conquest, Tarquin greatly expanded the borders of Rome by conquering the neighbouring tribes: the Latins, the Sabines, and the Etruscans. He was the first Roman to celebrate his military campaign with a triumph procession. Finally, he left a lasting mark on Rome with his building projects. He commissioned the building of the Circus Maximus, the Cloaca Maxima sewage system, and the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill.

6. Servius Tullius

(Wikimedia Commons)

The sixth king of Rome was Servius Tullius, the son in law of Lucius Tarquinius Porcus. Early in his reign, he achieved military success against the Veii and the Etruscans, which he celebrated with three triumph processions. Additionally, he expanded border of Rome to include the Quirinal, Veminal and Esquiline hills. As for politics, Servius introduced major administrative reforms, extending voting rights for plebeians by establishing a census (i.e. the registration of a one’s wealth, tax liabilities, military obligations, and the value of his vote) of every male citizen to determine their rights and duties. He furthermore eroded the aristocracy’s power by replacing their comitia curiata by the comitia centuriata, an assembly of commoners, as the central legislative body. It heavily diminished the power of the aristocracy, since the comitia curiata now could do little more than ratify the decisions of comitia centuriata. Servius was cruelly murdered by his son-in-law Lucius Tarquinius Superbus who usurped the kingship.

7. Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

(Wikimedia Commons)

The seventh and last in the line of kings was Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (‘Tarquin the Proud’), the son or grandson of Tarquinius Priscus. Tarquin was the opposite of his predecessor Tullius. He was vain, arrogant, and contemptuous of the people and the senate. He ruled as an absolute tyrant, using fear and oppression to remain in power, while completely dismissing the senate. To make matters worse, his son Sextus was just as corrupted as is father. When visiting his cousin Collatinus, he fell in love with his spouse, Lucretia. He later secretly came back to the house and forced himself upon her. Lucretia was overwhelmed by shame and, after telling her father and husband what happened, drew a concealed dagger and stabbed herself in the heart.

When rumour spread about this horrific deed, Lucretia’s husband Tarquin Collatinus and Lucius Junus Brutus organised revolt a revolt and eventually succeeded in expelling Tarquin Superbus. Horrified by the tyrannic rule of the last king, the comitia centuriata decided that Rome’s power should never again fall into the hands of one man. And so they agreed that two men should be elected annually to rule over the city. The leaders of the revolt would become the first two consuls: Tarquin Collatinus and Junus Brutus. Thus, the Roman monarchy was abolished in favour of a Roman Republic, lasting for almost five centuries, until Augustus rose to power in 27 BC.

Further Reading

As for ancient texts, our main sources on the Roman kings are: Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita, Cassius Dio’s Roman History, and Plutarch’s Parallel Lives. As for secondary sources, Tim Cornell’s The Beginnings of Rome (1995), Gary Forsythe’s A Critical History of Early Rome (2005), and Kathryn Lomas’ The Rise of Rome (2018) seem to be reasonable choices.