Hermann Hesse (1877-1962) was a German-Swiss poet and novelist. Born in the Black Forest town of Cawl, in southern Germany, as the son of an Estonian father and French-Swiss mother, Hesse experienced from a young age what it meant not fit in. While, according to his mother, the young Hesse showed “an unbelievable strength, a powerful will, and, for his four years of age, a truly astonishing mind”, he suffered signs of severe depression already in his first year of school. He was not an easy child, refusing to be subdued. Wanting to pursue a literary career, Hesse continued to struggle after school.

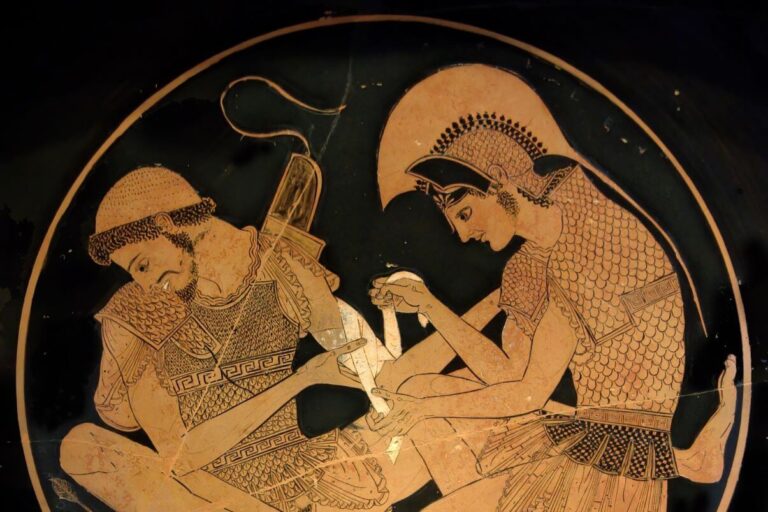

(Wikimedia Commons)

“I spent most of my school years in boarding schools in Wuerttemberg and some time in the theological seminary of the monastery at Maulbronn. I was a good learner, good at Latin though only fair at Greek, but I was not a very manageable boy, and it was only with difficulty that I fitted into the framework of a pietist education that aimed at subduing and breaking the individual personality. From the age of twelve I wanted to be a poet, and since there was no normal or official road, I had a hard time deciding what to do after school.”

Hermann Hesse, from the banquet speech after winning the 1946 Nobel Prize of Literature

Despite struggling early on his career, Hesse eventually found commercial success. His first acclaimed work was Peter Camenzind (1904), which narrates the story of a young, increasingly disillusioned man who suffers terribly after various failed romances and artistic endeavours. It is not hard to see that this novel, which was a favourite of none other than Sigmund Freud, is strongly autobiographical. In his works, Hesse explored the human struggle for meaning, authenticity, and spirituality. This search for meaning in part reflects Hermann Hesse’s own struggle, as stated by the translator David Horrocks.

“By the time Steppenwolf was published in 1927, Hesse’s well-established intellectual nonconformism had taken its toll. A feeling of having excluded himself irreversibly from a disgusting, laughable contemporary world was evident in his autobiographical notes (…). The sense of irremediable loneliness and a suicidal repulsion by modern realities are depicted in the form of the midlife crisis experienced by the central character of Steppenwolf, Harry Haller.”

David Horrocks, from the afterword of his 2012 Steppenwolf translation

These themes, the inability to fit in, the struggle to find one’s place in modern society, would also permeate his later works, like Demian (1919), Siddharta (1922) Steppenwolf (1927), and Narcissus and Goldmund (1930). These works would attain great acclaim throughout the 20th century. In 1946, he even won the Nobel Prize in Literature “for his inspired writings which, while growing in boldness and penetration, exemplify the classical humanitarian ideals and high qualities of style.”

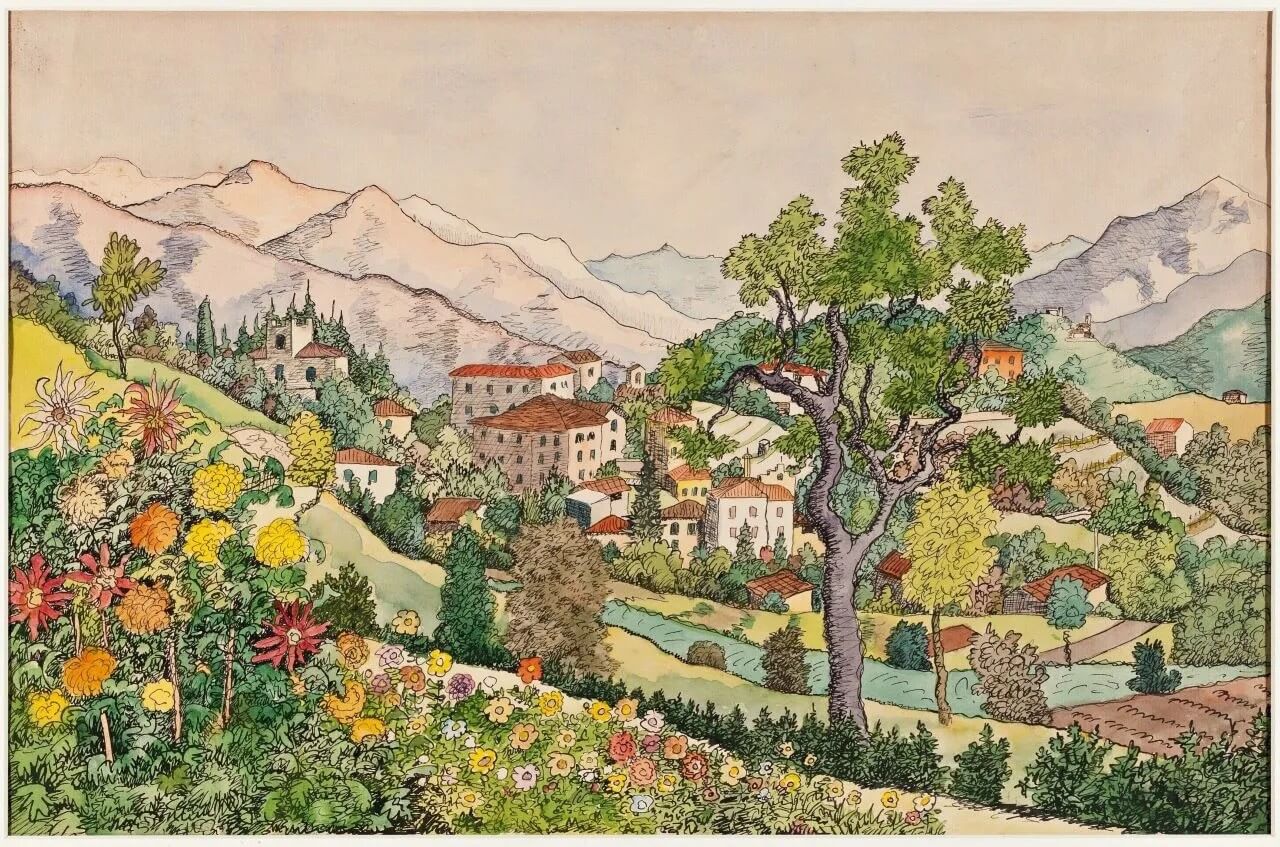

Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse

Summary

Steppenwolf for the most part is an embedded narrative, a story within a story. A large part of the book consists of what is said to be a manuscript written by the protagonist, Harry Haller, called ‘Harry Haller’s Records (For Madmen Only)’. Not coincidentally bearing the same initials as Hermann Hesse, Harry too is someone who does not fit in with the rest of modern society, who is condemned to an isolated life of self-hatred and self-contempt.

“During that period I became increasingly aware that the illness he was suffering from didn’t stem from any deficiencies in his nature. On the contrary, he had strengths and talents in abundance, but had never managed to combine them harmoniously, and that was his only problem. I came to realize that Haller had a peculiar genius for suffering, that he had, in the sense that Nietzsche intends in many of his aphorisms, trained himself to the point where his capacity for suffering was masterly, limitless, awesome.”

He despises the bourgeois for their low aspirations and the hollow ideals, but he secretly yearns to be just like them, to have a normal job, safety, and comfort. His life consists of reading books and aimlessly wandering about the city till the late evening hours, all the while drowning his sorrow with a couple of bottles of wine. Even though he is able to keep up appearances with his landlady and old acquaintances, deep down he is miserable.

“Solitude is independence. It had been my wish and with the years I had attained it. It was cold. Oh, cold enough! But it was also still, wonderfully still and vast like the cold stillness of space in which the stars revolve.”

Living between hope and fear, he feels superior to the shallow bourgeois and inferior as an outcast. That is, until he stumbles upon a mysterious pamphlet called Treatise of the Steppenwolf. The pamphlet addresses Harry directly and it tells the uncanny story of a man of two natures: a high nature, spiritual and cultured, the other nature low and beastly, like a wolf of the steppes. Hence the name, Steppenwolf. Furthemore, the pamphlet says that such people are fated to take their own life eventually. Caught up in a similar irremovable struggle, Harry falls into despair and at last even decides to take his own life.

“My decision to die was no passing whim, but a fruit that had ripened and would keep. It had grown slowly and was heavy now, gently rocked by the wind of fate and bound to fall when the next gust came along.”

While wandering through the city, trying to postpone the moment of his death, he stumbles upon a sparkling girl called Hermine. From here, against all odds, his life is making a clear turn. Hermione introduces Harry to the buzzing world of jazz music – note that the book is taking place in the Roaring Twenties -, to dancing the ‘foxtrot‘, to drugs, and to Maria, who would become his lover. Until then, Harry had abstained from sensual pleasures, had never danced, and had despised jazz music as inferior to classical music.

Harry learns that Hermione is the first person to truly understand him, with his inability to fit in, and his dissatisfaction with the shallow world of the bourgeois, devoid of any higher aspirations or ideals, devoid of any appreciation of true art.

“Whoever wants to live and enjoy his life today must not be like you and me. Whoever wants music instead of noise, joy instead of pleasure, soul instead of gold, creative work instead of business, passion instead of foolery, finds no home in this trivial world of ours.”

The books ends in a hazy scene, almost like a dream. After Hermione and Harry danced their last dance at a masked ball, they are finally taken to the metaphorical Magic Theatre, a sort of house of mirrors, where one can relive past events and experience the fantasies of the mind. It is a reflective journey inwards, into one’s own soul, one’s own nature. In this dream-like scene, Harry ends up killing Hermine, who had been a mirror for himself. The desire to kill her sprang forth from the desire to take his own life, to let go of his other self. It marks the end of Steppenwolf and a new beginning for Harry.

Themes

Steppenwolf is both tragic and triumphant, relatable and alienating, thrilling and horrifying. Such oppositions are central to the book. Harry, the protagonist, does not know whether he wants to live or wants to die. He despises the bourgeois, but at the same time he yearns to be one of them, to be normal rather than an outcast. He feels superior to others, but his self-hate is all-encompassing. The implicit premise of the book is that we, humans, contain multitudes. We are multifaceted, just like Harry is both human and Steppenwolf. Rather than choosing one over the other, we are forced to contain contradictory natures, thoughts, and feelings. It is the reason cognitive dissonance exists. Only when we come to terms with all our different natures, do we truly attain inner peace.

Conclusion

Steppenwolf was the third book of Hermann Hesse I read, after Narcissus and Goldmund and Demian, all of which I can heartily recommend. At first I was not sure whether I could handle another book on despair and isolation after recently reading Crime and Punishment, but I was soon enchanted by the poetic and introspective nature of Hesse’s writing. It is not difficult to see how Harry Haller corresponds to Hermann Hesse himself, who also felt secluded, disillusioned, and desperate at various stages of his life, which he would later regret.

“It led to regrets that he had spent so much of his younger years in the pursuit of some kind of higher wisdom, thus missing out on the simpler, unreflective enjoyments of life. In his own words, he was now attempting to live for once like an ‘overgrown child’.”

David Horrocks, from the afterword of his 2012 Steppenwolf translation

We, as a reader, have the ‘pleasure’ to read what he is going through, what he is thinking, and how he tries to cope with finding his place in the world. At this stage of my life, it was interesting reading this book. I too often wonder whether I am doing the right thing, reading books and pursuing the arts in favour of bourgeois pleasures. I hope I will not become like Harry Haller, but in some way, we all have to struggle finding our place in the world, intellectual, bourgeois, or anything else. We all have to struggle. That’s life.