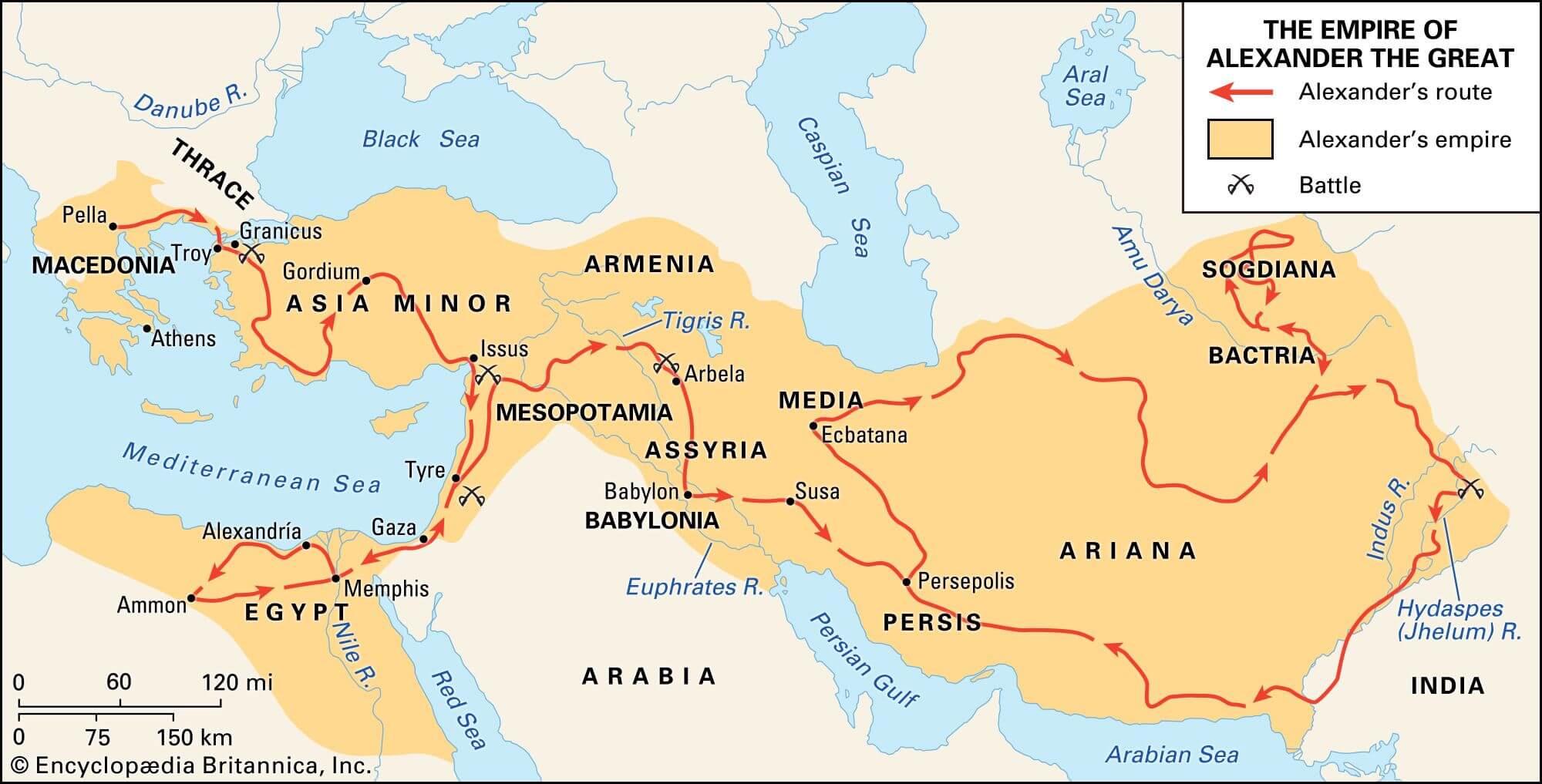

Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) is generally regarded as one of history’s most successful leaders and military commanders. He single-handedly changed the course of history by shaping an empire that stretched from Greece all the way to India. Already in antiquity, right from the moment he died, he was seen as the quintessential role model for every general, admired especially for his military prowess. It was for this reason that figures like Pompey the Great willingly assimilated themselves to Alexander.

Early Life

Alexander the Great was born in 356 BC in Pella, as the son and heir of Philip II, who at the time was the king (basileus) of the ancient kingdom of Macedon. He was raised in way typical for high-born youths at the time, learning to read and write, to play the lyre, to ride, and to fend for himself in combat. However, if we are to believe Plutarch, Alexander showed more interest in the arts than in athletics, a skilled fighter though he was (Plut. Alex. 4). Still, his composure, self-discipline, and desire for recognition were apparent already when he was a child. This is epitomized in the famous story of Alexander taming Bucephalus. When a horse trader named Philonicus offered the horse Bucephalus to Philip for a hefty sum, the king bluntly refuses the offer, as the horse seemed uncontrollable. While his father was not interested, Alexander wagered that he would be able to tame the horse, ensuring he would pay the whole sum if he failed to do so. What happened next is thus portrayed by Plutarch.

“Alexander ran over to the horse, took hold of the reins, and turned him to face the sun—apparently because he had noticed that the horse was made jittery by the sight of his shadow stretching out and jerking about in front of him. He ran alongside the horse for a short while, caressing him, until he saw that he was bursting with energy and that his spirit was up, at which point he unhurriedly shrugged off his cloak, jumped up, and sat safely astride him. Then he pulled a little on the bit with the reins and kept him in check without hitting him or tearing his mouth. When he saw that the horse was no longer a threat and was eager for a gallop, he gave him his head, urging him on more stridently now, and kicking with his heels. At first Philip and his companions were in an agony of silent suspense, but when Alexander made a perfect turn and started back jubilant and triumphant, everyone else cried out loud, but his father—so we are told—actually shed tears of joy, and when Alexander had dismounted he kissed him on the head and said, ‘Son, you had better try to find a kingdom you fit: Macedon is too small for you.’”

Plutarch, Alexander 6 (trans. Robin Waterfield)

It is difficult to assess to what extent such anecdotes are accurate, since our most important sources, Quintus Curtius Rufus, Plutarch, and Arrian, all wrote centuries after Alexander’s death. But, in the words of Giardano Bruno, se non è vero, è ben trovato (‘even if it is not true, it is well conceived’). Nonetheless, there is surely some truth in these anecdotes, that he was destined for greatness and that he was of exceptional character, since his later deeds were nothing short of miraculous. In part, he thanked his exceptional character to his exceptional tutor. At the age of thirteen, Alexander was assigned by his father the most famous and learned of all philosophers: Aristotle. Together with other Macedonian nobles, such as Ptolemy and Hephaestion, who would later become his close friends, Alexander was taught in the matters of medicine, philosophy, and art. From Aristotle, he received his political and ethical doctrines, and most of all his passion for literature, especially the Iliad, which he always kept under his pillow.

“He regarded and referred to the Iliad as a handbook on warfare, and carried about with him Aristotle’s recension of the text, which he called ‘the Iliad of the casket’ and always kept under his pillow along with his dagger, according to Onesicritus. When he was deep in Asia and had no access to any other books, he told Harpalus to send him some, and Harpalus sent him Philistus’ works, a lot of tragedies by Euripides, Sophocles, and Aeschylus, and the dithyrambic poetry of Telestes and Philoxenus.”

Plutarch, Alexander 8 (trans. Robin Waterfield)

At the age of eighteen, Alexander got into a dispute with his father, after being called a bastard by Philip’s friend Attalus – for Philip had recently remarried and begotten a son and possible new heir. While father and son were eventually reconciled, Alexander’s position as heir now was jeopardized.

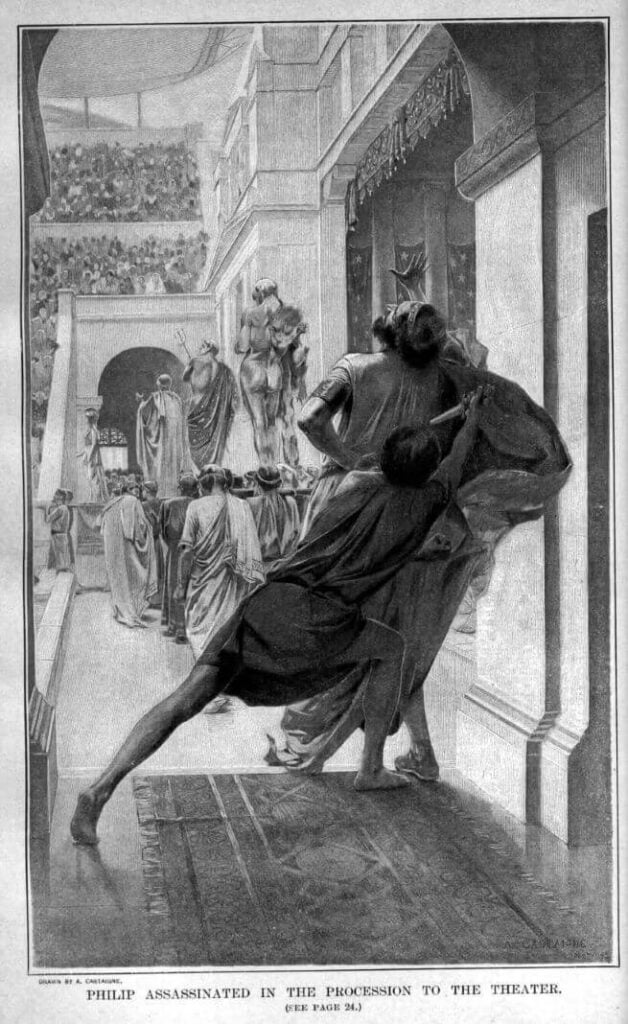

It is for this reason that, when Philip was assassinated in 338 BC, some people suspected Alexander of having conspired against his father. The story goes that Philip was killed by the captain of the bodyguards, Pausanias, during the procession of his daughter’s wedding. Thus, Alexander rose to power by inheriting the throne of Macedon at the mere age of twenty.

The Conquest of Alexander

After eliminating potential rivals to the throne, Alexander had to subdue many states which were revolting after the instability ensuing Philip’s death. Alexander responded quickly by suppressing the tribes up to the natural border of the Danube, after which he marched on Thebes in the south. When they refused to surrender and put down their arms, Alexander made an example of them and razed the whole city to the ground. Afraid of meeting a similar fate, Athens surrendered to Macedon, so that Greece was at peace for the moment. Leaving Antipater behind as a regent for the region, Alexander could finally begin his expedition against Persia.

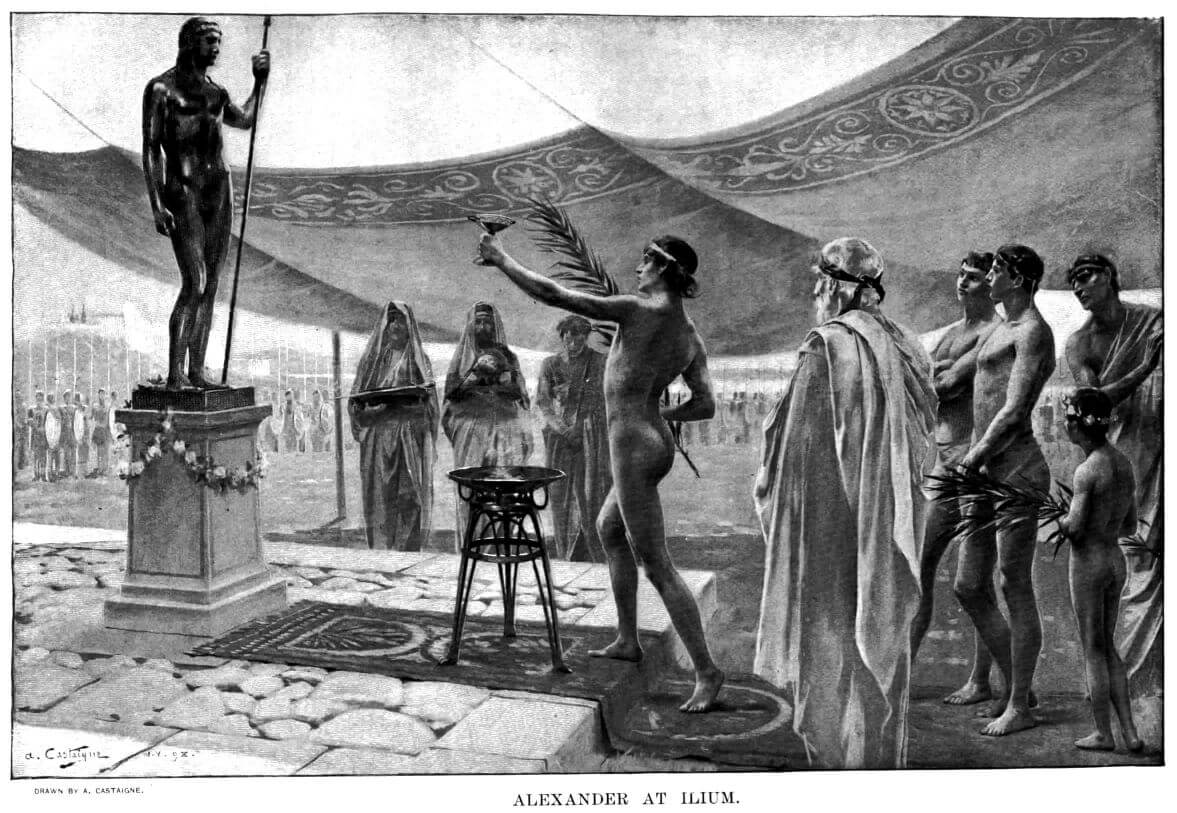

Alexander crossed the Hellespont (hellespontos, ‘sea of Helle’) in 334 BC to enter Asia Minor, taking with him an army of around 40,000 infantrymen and 5,000 cavalry. But before he fully began his campaign, he set off to visit Troy, to honour the hero from his cherished Iliad, Achilles.

“At Troy, he offered up a sacrifice to Athena and poured libations to the heroes. At Achilles’ tombstone,† he anointed himself with plenty of oil, ran a foot-race, naked as custom demands, with his Friends, and crowned the tombstone with a garland, pronouncing Achilles fortunate for the true friend he found during his lifetime and the great herald he found after his death. While he was walking about and seeing the sights of the city, someone asked him if he would like to see Alexander’s lyre; he replied that he had not the slightest interest in that lyre, but was looking for the one Achilles had used to sing of the glorious achievements of brave men.”

Plutarch, Alexander 15 (trans. Robin Waterfield)

After visiting Troy, Alexander was opposed by a considerable army of Darius at the crossing of the river Granicus. Nonetheless, he is told to have achieved an astounding victory over his opponents. Not only did he achieve his first victory, but he was also offered the surrender of Sardis, the capital of the Persian province. He went on to free many of the cities on the Ionian coast, such as Miletus and Halicarnassus (the birthplace of the historian Herodotus), from the Persian yoke. When he arrived in the ancient Phrygian capital of Gordium, Alexander famously undid the hitherto unsolvable ‘Gordian knot’, if we are to believe Plutarch.

“When the city of Gordium capitulated to him (…), he saw the famous cart with its lashing made out of the bark of a cornel tree, and heard the story which the natives there believe, that whoever undid the knot was destined to become the ruler of the whole world. Most writers say that since the ends of the knot were hidden, and since the strands were twisted and turned over and under one another time and time again, Alexander could not find a way to undo it, and so he cut through the knot with his sword until a number of ends were exposed.”

Plutarch, Alexander 18 (trans. Robin Waterfield)

Alexander soon ventured into Syria, where he defeated Darius, who had a notably larger army, at the battle of Issus. However, Darius fled the battle, not only causing the collapse of his army, but also leaving his wife and children behind to be captured by the enemy. Alexander was surprisingly mild and purportedly treated them even better than Darius did. Now he had taken possession of Syria, and having seized a large part of the Levant (from the French levant, ‘rising’, referring to the rising of the sun in the east), Alexander proceeded to conquer Egypt. There, he famously founded the city of Alexandria, named after himself.

“They say that after Alexander had conquered Egypt, he wanted to found, as a memorial, a major, populous Greek city, named after himself (…). There was no chalk to hand, so they took some barley and on a level patch of dark soil they marked out a circle whose lower arc was drawn up from its skirt, so to speak, until, by uniformly contracting the area, it formed the shape of a military cloak. Their royal master was delighted with the design, but suddenly a vast number of birds from the river and the lake, of all kinds and sizes—so many that it was as if a cloud passed across the sky—swooped down on to the place and devoured every last grain of barley. Even Alexander found this omen disturbing, but the diviners told him that there was no cause for alarm, because the city founded here by him would be self-sufficient to a very high degree and would supply the needs of all kinds of men, so he told his overseers to get on with the work.”

Plutarch, Alexander 26 (trans. Robin Waterfield)

Still not satiated after conquering Asia Minor, Syria, the Levant, and Egypt, Alexander set out for Mesopotamia, where he – this time decisively – defeated Darius, at the Battle of Gaugamela. Alexander could now easily venture further into the east, while taking possession of major cities like Susa and Persepolis that had capitulated after Darius’ defeat. Alexander purportedly gave his soldiers the command to plunder and slaughter the people of Persepolis, the former capital of the Persian empire, showing his more cruel side. It is suggested by some that the ensuing fire that would break out in Xerxes’ former palace was an accident, but others argue it was instigated by Alexander, avenging the burning of the Acropolis of Athens by Xerxes in the Second Persian Wars.

“When Alexander saw a colossal statue of Xerxes, which had been rudely knocked over by the press of the huge numbers of people forcing their way into the palace, he stood by it and said, as if he were talking to a living person: ‘Shall I leave you lying there, to pay for your expedition against Greece, or shall I wake you up because of your noble self-assurance and excellence in other respects?’ Eventually, after pondering the matter in silence for quite a while, he left the statue lying there and walked on.”

Plutarch, Alexander 37 (trans. Robin Waterfield)

Now the Persian empire had finally been subdued, now Alexander had even been hailed the new Great King of Persia, the fame and fortune had gone to his head. Like his role model, Achilles, hubris (hubris, ‘pride’) got the better of him. Already in Egypt, he claimed to be the son of the Ammon, the Egyptian equivalent of Zeus, when the prophet of Ammon greeted him in terms implying that the god was his father. Plutarch however seems to make fun of this incident.

“Some writers say that the prophet wanted, out of politeness, to address Alexander in Greek with the words ‘O paidion’, ‘My son’, but, not being a Greek-speaker, he made a mistake with a sigma at the ending and said ‘O paidios’ instead, substituting a sigma for the nu. Alexander, they say, was delighted with this slip in pronunciation, and word got out that the god had addressed him as the son of Zeus, O pai Dios.”

Plutarch, Alexander 27 (trans. Robin Waterfield)

Alexander furthermore began to wear the Persian royal dress and to adopt Persian customs, most notably the custom of proskynesis (proskýnēsis, ‘a solemn gesture of respect for the gods and people’, like prostration). While Alexander likely adopted these Persian practices in part to appease the Persian nobles, the Macedonian troops became increasingly uncomfortable with Alexander’s deification and Persian customs. There had even been plans among the troops to assassinate their commander, but these were revealed in time and its conspirators were put to death. Despite of all these setbacks, Alexander still went ahead with his conquest of the world. In 326 BC, Alexander invaded India, where he only narrowly defeated the mighty army of Porus, who famously charged the Macedonian forces with his war elephants. Initially, Alexander had planned to cross the river Ganges, but when his worn-out troops mutinied and refused to march further east, he finally gave in and began to prepare their return.

“Alexander shut himself up in his tent and lay there in sullen anger, refusing to feel any gratitude for what he had already achieved unless he could cross the Ganges as well; in fact, to his way of thinking, withdrawal was the same as an admission of defeat.”

Plutarch, Alexander 62 (trans. Robin Waterfield)

Death and Legacy

One of the last things Alexander would do, was visiting the tomb of Cyrus the Great, which he heard had been desecrated. He had admired Cyrus the Great since he was a boy reading Xenophon’s Cyropedia. Therefore, he now wanted to pay tribute to Cyrus, by ordering the tomb to be restored and decorated.

“When he discovered that the tomb of Cyrus had been broken into, he had the person who had committed the crime put to death, even though the culprit was an eminent Macedonian from Pella called Poulomachus. After reading the inscription on the tomb, he had a Greek version transcribed underneath the original. This is how the Greek version reads: ‘Sir, whoever you may be and wherever you may be from, know that I am Cyrus, who gained the Persians their empire. Therefore do not begrudge me this earth which covers my body: it is not so very much.’ This reminder of the uncertainty and instability of things profoundly moved Alexander.”

Plutarch, Alexander 69 (trans. Robin Waterfield)

By honouring Cyrus as he honoured his other role model, Achilles, at the start of his career, Alexander was thus coming full circle, unifying the West and the East in himself. When he died in 323 BC, at the age of 32, Alexander left behind an empire stretching from Greece to India, the like of which the world had never been seen before. Besides conquering half of the known world and founding countless cities bearing his own name, Alexander was responsible for Hellenizing the territories he conquered. His death marks the beginning of what we call the Hellenistic period, in which Greek language, culture, religion, and identity spread throughout Alexander’s former empire, giving rise to a cultural fusion of the West and the East. Even though there is much we simply do not know about him, he still manages to capture our imagination. Like Pompey the Great, Caesar, and Augustus, we too – even today – still marvel at his miraculous achievements.

Further Reading

As for further reading, I would recommend going straight to the sources (ad fontes). Our main sources are Plutarch, for a very entertaining account of Alexander’s life, and Quintus Curtius Rufus and Arrian, for a more detailed account of his military campaign.

You cannot go wrong with any of the Oxford World’s Classics or Penguin editions. I personally enjoyed Robin Waterfield’s translation of Plutarch. If you have a predilection for historical fiction, I can heartily recommend Mary Renault’s Alexander Trilogy as well.