Sing, goddess, the anger of Achilles. These are the first words of the Iliad. Together with the Odyssey, it is the earliest and greatest work of literature from classical antiquity. Written around the 8th century BC and attributed to the Greek poet Homer, the Iliad is an epic poem about the city of Troy (Ilion) – and more specifically, about Achilles’ wrath. Alexander the Great famously slept with a copy of the Iliad under his pillow. And to this day, the Iliad still stirs our imagination, teaching us what it means to live and to die.

(Wikimedia Commons)

“Vivid, painful, and direct, the Iliad is one of the most influential poems of all time. It has continuously featured in the school curriculum for two-and-a-half millennia; and, even before then, audiences regularly heard it performed at public festivals and in private houses. (…) This poem confronts, with flinching clarity, many issues that we had rather forget altogether: the failures of leadership, the destructive power of beauty, the brutalizing impact of war, and our ultimate fate of death. That the Iliad has been so widely read is not just a testament to its immense power. It also speaks of the commitment of its many readers, who have turned to it in order to understand something about their own life, death, and humanity.”

Barbara Graziosi, from the introduction of Anthony Verity’s 2011 translation of the Iliad

As we read in its opening lines, the Iliad recounts Achilles’ wrath, not the Trojan war in general. In fact, the poem does not contain all the famous stories we associate with Troy. The judgement of Paris, the Trojan horse, and even the fall of Troy itself are not recounted in the poem. Instead, the Iliad describes a period of just two weeks in the tenth and final year of the Trojan War. Starting in the middle of things (in medias res), it begins with Achilles’ quarrel with Agamemnon and ends with Hector’s funeral. It concludes not with martial triumph, but with a heartbroken Achilles accepting that he will lose his life in this pointless campaign. While the Iliad contains many battle scenes, it does not glorify killing, nor does it cover up the cruelty of war. On the contrary, it shows the very real consequences of war, touching upon the themes of loss, suffering, and death. Ultimately, the Iliad explores what it means to be subjected to fate and the human tragedy of war.

Background

There is a lot of uncertainty regarding Homer and his writings. According to tradition, he was a blind bard hailing from the island of Chios or the city of Smyrna, both around the west coast of modern-day Turkey, but these accounts are likely unfounded. We cannot even be certain that Homer existed at all. However, in the ongoing debate, dubbed the ‘Homeric Question’, there is reasonable consensus that Homer represents the moment in time when the oral tradition became a written text. So, while the Iliad as we know it has been written down around the 8th century BC, there was a strong oral tradition long before Homer in which the poem took shape, possibly going back to the 13th century BC, to the period of the historical Trojan war. Thus, the Iliad functions as a filter of a long forgotten world, containing fossilized memories of Mycenaean Greece, a period that Hesiod identified as the Heroic Age, a past that must have been mythical even to Homer.

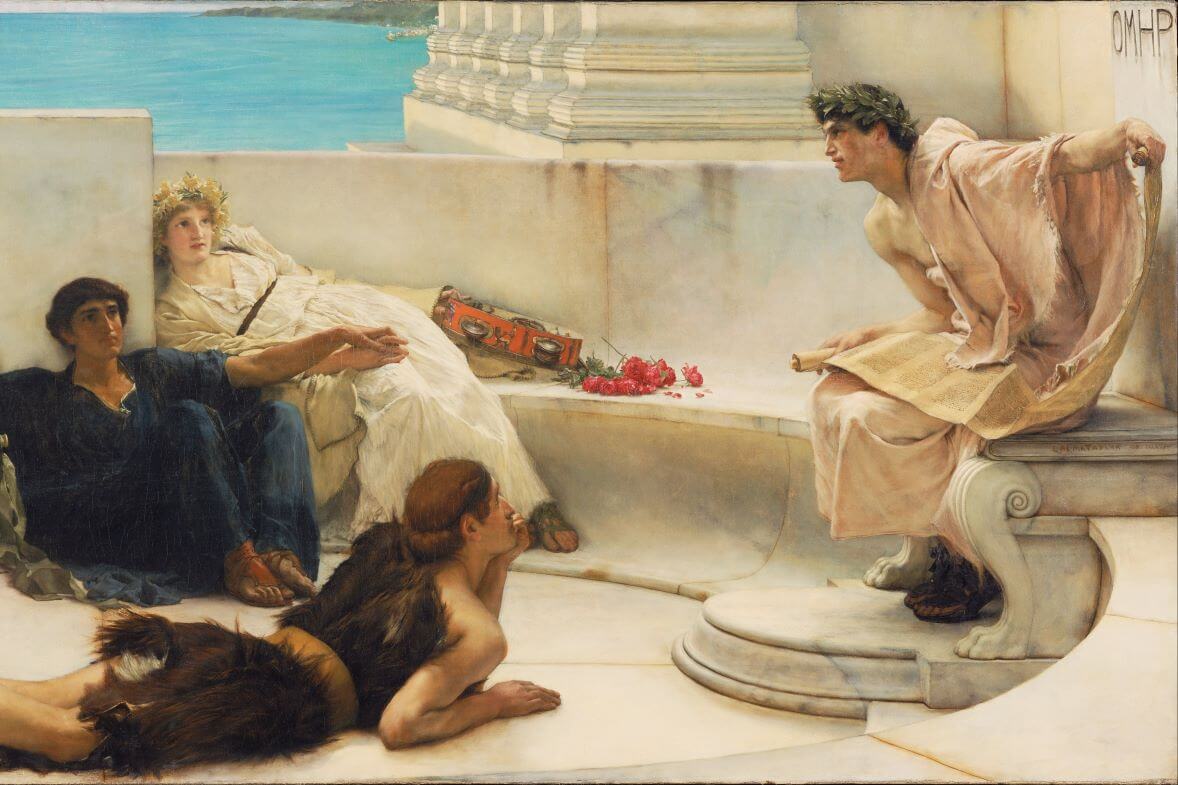

Note that these epic poems were not meant to be read, but rather to be performed by professional singers (aoidoi). Traveling the country, they would perform these poems not only at courts, to entertain the kings and nobles of their day, but also at certain festivals, such as the Panathenaic Games. They were trained to perform the poems by heart, improvising as they pleased, while relying on a semi-fixed substructure of narrative, meter, and repetition. They would use these repetitive expressions, known as formulas, as building blocks they could fall back on during improvisation. Thus, there was not one version of the Iliad or the Odyssey. For our version of the text, Homer likely combined and unified elements from various different retelling of the story.

Homer’s poetry is partly characterized by the aforementioned formulas, especially the so-called epithets (epitheta ornantia), adjectives that were repeatedly used to describe certain figures, places, or phenomena, such as: rosy-fingered Dawn, swift-footed Achilles, and Hector of the shining helmet. Another feature of Homer’s poetry is the Homeric simile, a detailed comparison of an element in the story with something else. They often occur at the height of action, taking us back from the battlefield to reflect on what we have read. These similes suffuse the poem with a striking vividness and empathy, making us contemplate the events of the Iliad as more than a mere story.

As is the family of leaves, so it is also with men:

Homer, Iliad 6.146-149 (trans. Anthony Verity)

the wind scatters the leaves on the ground, but the forest breaks

into bud and makes more when the spring season comes round.

So with the family of men, one generation grows and another ceases.

The Iliad

Sing, goddess, the anger of Achilles, Peleus’ son,

Homer, Iliad 1.1-7 (trans. Anthony Verity)

the accursed anger which brought the Achaeans countless

agonies and hurled many mighty shades of heroes into Hades,

causing them to become the prey of dogs and

all kinds of birds; and the plan of Zeus was fulfilled.

Sing from the time the two men were first divided in strife –

Atreus’ son, lord of men, and glorious Achilles.

After invoking the muse for divine inspiration, Homer clearly announces the subject matter of his writing in the introduction (prooemium). He will sing of ‘the anger of Achilles’, an anger that would make him wreak havoc on the battlefield, mercilessly killing countless Trojans and leaving their bodies to rot. Denying them a proper burial, he transgresses the boundaries of honourable behaviour, even if he is a hero. But it is not Achilles who it to blame, Homer implies, for it is fate that decides the course of history. Or, as Homer puts it, it is ‘the plan of Zeus’.

In the end, not we, but the gods decide what happens to us. The underlying idea is that no one can escape one’s fate. We have to deal with what is given to us. And that is also the idea of the Iliad. We simply have to accept what happens to us, no matter how hard, for we cannot control the course of our lives. Having made this clear, Homer announces that he will now begin his tale, starting from the first moment that Achilles clashed with his commander Agamemnon. Homer assumes that we already know what precedes this strife, namely: the judgement of Paris, Paris abducting Helen, the Greeks declaring war to avenge her, the sacrifice of Iphigenia, and the long siege of Troy.

Summary of the Iliad

Book 1-8: Achilles Abstains From Fighting

Book 1: The strife between Achilles and Agamemnon begins as a matter of honour. When Agamemnon demands Achilles’ slave and war prize Briseis, Achilles is offended in his honour and furiously declares that he will no longer fight for Agamemnon, while asking the gods to help him.

‘One day longing for Achilles will come upon the sons of the Achaeans,

Homer, Iliad 1.239-244 (trans. Anthony Verity)

every one of them; and then, for all your grief, you will have no power

to help them, when many fall and die at the hands of man-slaying

Hector; and you will tear apart the heart within you in anger,

because you denied all honour to the best of the Achaeans.’

Book 2: Zeus contrives a plan to help Achilles: sending a dream to Agamemnon that urged him to launch an attack, he would make the Greeks suffer great losses as long as Achilles was not fighting.

Book 3: Before both armies meet, Paris challenges Menelaus to a duel to decide who is worthy of Helen. When Paris is beaten, however, Aphrodite rescues him from certain death.

Book 4: The gods discuss the developments on the battlefield. Zeus proposes a peace treaty after the duel, but Hera and Athena furiously disagree, for they will not rest until Troy lies in ruins.

Book 5: Diomedes has his moment of glory on the battlefield (aristeia). The Greek hero kills many Trojan warriors and defeats the Trojan prince Aeneas, who is saved from death by Aphrodite.

Book 6: After rallying the Trojans, Hector enters the city to reproach Paris for not fighting. In a moving scene, he bids farewell to his wife Andromache and son Astyanax before rejoining battle.

Book 7: Hector duels with Ajax, until both sides retire at nightfall. The Greeks build a wall.

Book 8: The Trojans make progress in battle, eventually reaching the walls of the Greek camp.

Book 9-16: The Greeks Are Losing

Book 9: The Greeks are quickly losing ground. Agamemnon desperately attempts to appease Achilles by returning Briseis, but Achilles’ anger has not cooled, and he refuses to enter battle.

Book 10: At night, Odysseus and Diomedes venture out to spy on the enemy lines. They wreak havoc in the camps of Troy’s Thracian allies, killing the Trojan spy Dolon on their way.

Book 11: The next morning, Agamemnon enjoys his moment of glory on the battlefield (aristeia), killing countless Trojans. Nestor urges Patroclus to beg Achilles to rejoin the fighting, or if that fails, that Patroclus himself would lead the troops, wearing Achilles’ armour to boost their morale.

Book 12: The Trojans, led by Hector, successfully advance to the Greek wall and breach the gate.

Book 13: Poseidon pities the Greeks and helps them to push back the Trojans from the ships.

Book 14: The Greeks drive the Trojans back to the plain and Ajax manages to wound Hector.

Book 15: When Zeus wakes up, he puts Poseidon’s plans to a halt and sends Apollo to help the Trojans, who this time manage to push back the Greeks all the way to their ships.

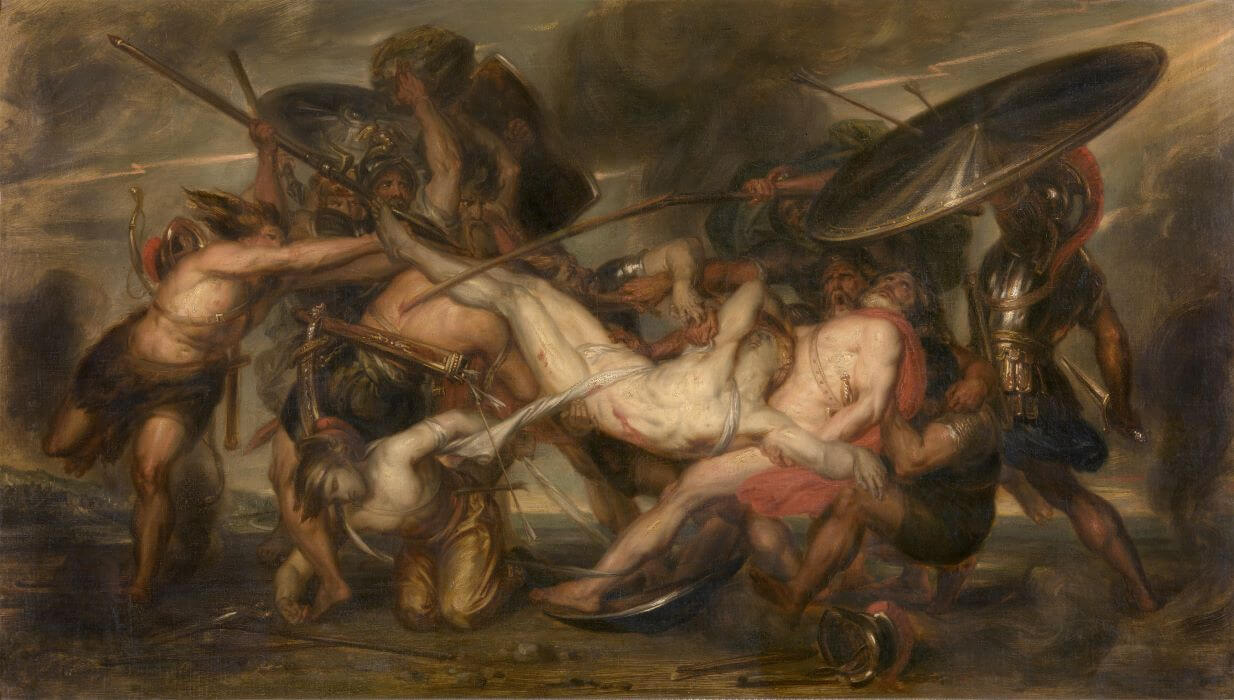

Book 16: Patroclus begs Achilles to allow him to fight in his stead, in his armour, for it will restore the morale of the troops. Achilles reluctantly gives in, on the one condition that Patroclus will not chase the Trojans too far. But fate willed otherwise. After experiencing his final moment of glory (aristeia), he pushed his luck (hubris) and advanced all the way to the Trojan gate. There, he is eventually killed by Hector – not because Hector was stronger, but because the gods ordained it so.

‘Boast loudly while you can, Hector; Cronus’ son Zeus and Apollo

Homer, Iliad 17.844-849 (trans. Anthony Verity)

have given you the victory, they who have beaten me down

easily – for it was they who stripped the armour of my shoulders.

But if twenty men such as you are had come to confront me

they would have died here and now, beaten down by my spear.

No, it was my fatal destiny and Leto’s son that killed me.’

Book 17-24: Achilles Takes Revenge

Book 17: Menelaus fends off the Trojans and with difficulty is able to protect Patroclus’ corpse.

Book 18: When Achilles hears of Patroclus’ death, he is both devastated and seething with rage. The only thing he wants do is to kill the man who slaughtered his friend. Only after he has killed Hector, will he perform the burial rites to Patroclus. Meanwhile, the god Hephaestus has made him a magnificent new set of armour at the request of Achilles’ mother, the sea goddess Thetis.

Book 19: Putting on his new armour, Achilles prepares for battle, knowing that he is fated to die.

Book 20: Entering the fray, Achilles is besides himself from rage and slays countless enemies.

Book 21: Achilles in his blind rage even challenges and duels the river god Scamander.

Book 22: By now, all Trojans have retreated behind the city walls, seeking refuge from Achilles’ fury – except for Hector. But he did not stand a chance, for the gods had already sealed his fate. After three times chasing Hector around the walls of Troy, Achilles kills him and dishonours his corpse by dragging it around the city walls for all Trojans to see. This was Achilles’ revenge.

Book 23: The next morning, Patroclus’ ghost appears to the sleeping Achilles, urging him to carry out his burial rites, so he can at last rest in peace. Finally, he asks for them to be entombed in a single urn, so that they may be together in death as they were in life. Achilles is moved and does as he was asked. That day, the Greeks held funeral games in honour of their beloved Patroclus.

‘Give me your hand, I beg you; I will not come again

Homer, Iliad 23.75-92 (trans. Anthony Verity)

from Hades, once you have granted me the due rite of fire.

Never again in life shall we two sit apart from our companions

and make our plans together, for over me gapes the hateful

death-spectre which was appointed me right from my birth.

And for you too, godlike Achilles, your destiny is fixed,

to meet your death below the walls of the noble Trojans.

And I say another thing to you, a request, if you will agree:

do not lay my bones in a different place from yours, Achilles,

but together, just as we were brought up in your house,

(…) may one and the same vessel hide the bones of us both,

the golden, two-handled jar that your revered mother gave you.’

Book 24: Achilles is inconsolable, unleashing his grief and anger on Hector’s corpse. At last, Zeus decides that it should stop. He sends Hermes to secretly guide the Trojan king Priam to the Greek encampment in the middle of the night. Having arrived at Achilles tent, Priam enters and clasps Achilles’ knees, begging for his son’s body and reminding Achilles of his own father. Achilles breaks down in tears and agrees to return Hector’s body, so that he too, like Patroclus, can receive the burial rites necessary to cross threshold of Hades. Thus, the Iliad ends with Hector’s funeral.

Analysis

The most recurrent themes of Homer’s Iliad are honour, death, and fate. In fact, it is the relation between these three matters that Homer so movingly explores. Should we sacrifice our lives for our country, should we let others suffer because of sense of pride, and is it worth dying for eternal glory? Or should we not delude ourselves into thinking that we can alter our fate in the first place? It is this inquiry into the human condition that makes Homer’s Iliad so remarkable. And it is for this reason that Horace called Homer a wiser teacher than all philosophers combined (Epistles 1.2). The Iliad is not a one-sided war-story of right and wrong. There are no clear-cut answers.

Instead, Homer invites us to explore these matters for ourselves. For example, Achilles disobeying his incompetent and shameless commander Agamemnon seems wholly justified, but is it still when so many of his countrymen are dying as a consequence? On the other hand, Achilles defiling Hector’s corpse and denying him a proper burial is a clear example of transgressive and appalling behaviour, but then you have to keep in mind that Achilles is blind with rage because Hector had killed his dear friend, Patroclus, the man whom he had known since childhood. His defiling of Hector’s corpse at the same time is a sign of his boundless love for Patroclus. Achilles is not simply ‘good’ or ‘bad’, but his behaviour is surely very human, so that we as a reader can identify with him. For, as with Achilles, our actions never exist in isolation. Functioning rather like a mirror, the Iliad offers us a space, a context, and a frame of reference to reflect on our own humanity. But as Simone Weil suggest, perhaps it is our tragic fate to never see ourselves for who we truly are. Maybe we, in our godless world, are just as much subjected to fate as Achilles, Patroclus, and Hector were.

“Perhaps all men, by the very act of being born, are destined to suffer violence; yet this is a truth to which circumstance shuts men’s eyes. The strong are, as a matter of fact, never absolutely strong, nor are the weak absolutely weak, but neither is aware of this. They have in common a refusal to believe that they both belong to the same species.”

Simone Weil, The Iliad or the Poem of Force (trans. Mary McCarthy)

I have earlier mentioned death and suffering as major themes in the Iliad, but I have not yet mentioned love. It is clear that love is also at the heart of the poem. In a way, one could frame the major themes of the Iliad as love and death, Eros and Thanatos, as coined by Freud. For it was not for glory, but for Patroclus that Achilles sacrificed his life. While it would be a stretch to say that Homer was a ‘make-love-not-war’ pacifist, it is telling that the Iliad ends not with celebration, but with the commemoration of the dead: the funeral games of Patroclus (Book 23) and the funeral of Hector (Book 24). Life is more precious even than glory, and we should think twice before putting our lives on the line, for what use is glory when we are dead? In a touching episode in Homer’s Odyssey, Achilles, now a shade in the underworld, expresses this very idea. For what did he sacrifice his life, he questions, for it was not worth it. If only he could come back to live another day.

‘Achilles, no man before has been more blessed than you, nor ever

Homer, Odyssey 11.473-491 (trans. Richmond Lattimore)

will be. Before, when you were alive, we Argives honoured you

as we did the gods, and now in this place you have great authority

over the dead. Do not grieve, even in death, Achilles.’

So I spoke, and he in turn said to me in answer:

‘O shining Odysseus, never try to console me for dying.

I would rather follow the plow as thrall to another

man, one with no land allotted him and not much to live on,

than be a king over all the perished dead.’