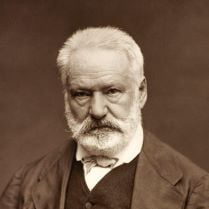

Victor Hugo (1802-1885) was a French novelist, poet, and politician, mostly known for his novels The Hunchback of the Notre-Dame and his magnum opus Les Misérables, both of which have enjoyed countless adaptations for musical, theatre, and television. While his father had been an officer in Napoleon’s army, Hugo was a committed royalist when young. Though, increasingly disenchanted with the monarchist rule, he eventually broke with the conservative party to join the republican cause. He became socially engaged and spoke out against social injustice, as a politician and a novelist.

(Wikimedia Commons)

“He shared with nearly all major writers the quality of abundance. The works poured out in an uneven flood, good, bad and indifferent, splendid at their best and, at their worst, lamentable: some twenty volumes of poetry (…), nine novels, ten plays (…), and a huge amount of general writing, literary, sociological and political. Hugo was always, in the French word, engagé, deeply concerned with the social and political developments of his time. His politics might change in the light of events and as a reflection of his own growth, but his essential position remained unchanged. He was first and foremost, by nature as well as by conviction, a romantic. It was an attitude to life expressing itself in all life’s activities, above all in the arts but also in politics, where it bore the name of liberalism.”

Norman Denny, from the introduction of his translation of Les Misérables

As Norman Denny states, Hugo’s works are characterized by ‘the quality of abundance’, which modern readers will likely deem a vice rather than a virtue. His alleged masterpiece, Les Misérables, is one of the longest novels ever written, with 655,478 words in the original French. One has to keep in mind it was towards the end of his career that Hugo wrote Les Misérables, and so, as an established and renowned writer, he had license to do as he please.

“[Hugo] had little or no regard for the discipline of novel-writing. He was wholly unrestrained and unsparing of his reader. He had to say everything and more than everything; he was incapable of leaving anything out. The book is loaded down with digressions, interpolated discourses, passages of moralizing rhetoric and pedagogic disquisitions.”

Norman Denny, from the introduction of his translation of Les Misérables

Most of these interjected digressions on a plethora of topics, like philosophy, history, geography, linguistics, or politics, often incoherent and detracting from the actual story, are indefensible. While his publisher, Lacroix, urged him to cut down on some of these sections, Hugo refused and published what may be called both a literary classic and an almost unreadable monstrosity.

Les Misérables

Background

In writing Les Misérables, Hugo was inspired by Eugène Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris, a serial novel that similarly viewed Paris from the perspective of the lower class, who until then had largely been neglected in literature. Hugo also drew inspiration from his own contemporary Paris, with its fair share of poor, sick, and homeless, noting down everything he heard and saw. The story of Jean Valjean, for example, was based on the ex-convict Eugène François Vidocq, who turned his life around to become a businessman and philanthropist. And having saved a prostitute from arrest for assault, Hugo used a part of their dialogue to describe Jean Valjean’s rescue of Fantine. He might even have envisioned himself as Marius, who also turned from a monarchist to a fervent republican. As for historical evidence, Hugo went out of his way to personally inspect the subjects of his writings, from the living conditions of the working class to the battlefields of Waterloo.

List of Characters

(Wikimedia Commons)

- Jean Valjean: the protagonist of our story, an ex-convict who turns his life around after meeting Bishop Myriel and adopting the orphaned child Cosette

- Javert: a fanatic police inspector incapable of compassion and pity who tirelessly tries to capture Jean Valjean

- Fantine: an innocent but naive working-class girl who is abandoned with her child, Cosette, by her sweetheart lover

- Cosette: the daughter of Fantine who is exploited by the Thénardier family but later adopted by Jean Valjean

- Marius Pontmercy: the son of a Napoleonic general fallen from grace, who is raised by his grandfather and who eventually falls in love with Cosette

- Monsieur and Madame Thénardier: a cruel, wretched, and greedy couple that exploits the poor Cosette and that later on continues to be a nuisance for Jean Valjean

Summary of Les Misérables

1. Jean Valjean

Les Misérables tells the story of the ex-convict Jean Valjean. After serving nineteen years in prison for the mere act of stealing a loaf of bread, he had turned from an innocent youth into a vengeful man, on whom society had turned its back. Upon his release, Valjean struggled to fit in due to his criminal record. Roaming the French countryside, he was only welcomed in the home of Monsieur Myriel, the Bishop of Digne. Even after stealing the bishop’s silverware, Myriel still treated him with compassion. Moved by the unconditional kindness of this almost saintly figure, Valjean promised to mend his ways and to become an honest man. From then on, he assumed the name Monsieur Madeleine, entered the manufacturing business in the town of Montreuil-sur-Mer, and eventually became a mayor. Eagerly using his money to do good, he vowed to help the poor and lonely, showing the same unconditional kindness that he had received from the bishop.

2. Fantine

One of the people he would help is Fantine, a young working-class woman who is struggling to get by, especially now she has been abandoned with her baby, Cosette, by her sweetheart lover. Realizing she will not find work if people know she has an illegitimate child, she hands over her child to the Thénardiers, a family that runs a local inn in Montfermeil. They promise to take care of her, on the condition that Fantine sends them a monthly allowance. Fantine then, by a twist of fate, finds work Madeleine’s factory, but is eventually fired when her co-workers find out about Cosette. The cruel Thénardiers demand more money, so that Fantine eventually resorts to prostitution to make ends meet. One day she is arrested by the fanatic police inspector Javert, but the mayor, Madeleine, intervenes and promises to take care of her and her child, but it was too late, because Fantine had taken ill and died soon after. Javert now had also taken an interest in this unknown benefactor, discovers that the local mayor is actually an ex-convict. Monsieur Madeleine, burdened by a guilty conscience, soon after confesses he is actually Jean Valjean.

3. Cosette

Having miraculously escaped from prison, Jean Valjean heads to Montfermeil to fetch Cosette, as he promised Fantine. He discovers that the cruel Thénardier family for years had abused Cosette, using her as a child servant. Jean Valjean and Cosette move to a poor neighbourhood in Paris, where they hope to be able to live under the radar. But even there, by a twist of fate, Javert is able to find them. After a nerve-racking pursuit, the two eventually find refuge in a Bernardine convent, where Cosette attends school and Valjean works as a gardener. Having laid low for a couple of years, they eventually move out to a place of their own, though still cautious of Javert.

4. Marius

On their daily strolls outside, catching some fresh air, they encounter a young man who seems to be particularly interested in Cosette, who had now blossomed into a beautiful young woman. While it was love at first sight, it was impossible for the two to meet, for Jean Valjean did everything in his power to protect Cosette from the outside world. The lovers are eventually united, but they are not given much time. Learning that their hiding place has been compromised, Jean Valjean decides to move from Paris, taking Cosette with her. Marius is heartbroken and, overcome with sadness, in a last act of heroism decides to join the June Rebellion. When all hope seems lost, and when most radicals have been killed, Jean Valjean miraculously appears on stage to save Marius from the clutches of death. In the meantime, he had spared Javert’s life, while he had the opportunity to end it. The rebellion failed, but the story of Jean Valjean ends well. Javert ceases his pursuit and commits suicide due to his guilty conscience, tormented between his duty and his debt to Valjean for saving his life. Cosette and Marius can finally marry and have a bright future ahead of him. At the end of the book, Cosette and Marius learn about Valjean’s true identity and all his good deeds. Happy to be reunited with Cosette, Jean Valjean thereafter dies in peace.

Conclusion

Finally, I am done with what possibly might have been my most excruciating reading experience, and more than once I was tempted to just give up on this classic. It is a mystery how such a bloated and unedited monstrosity of a book could have been published in this shape. The whole novel could have been reduced to less than four hundred pages without compromising the story in any way. There are countless incoherent digressions, philosophical contemplations, and needlessly interjected historical and geographical treatises, which are especially incomprehensible to the non-French, 21st-century reader. Nevertheless, the core story is very enthralling and Hugo’s genius does shine through at times, as well as his heartfelt plea for a fairer world, as in the following speech.

“Citizens, our nineteenth century is great, but the twentieth century will be happy. Nothing in it will resemble ancient history. Today’s fear will all have been abolished – war and conquest, the clash of armed nations, the course of civilization dependent of royal marriages, the birth of hereditary tyrannies, nations partitioned by a congress or the collapse of a dynasty, religions beating their heads together like rams in the wilderness of the infinite. Men will no longer fear famine or exploitation, prostitution from want, destitution born of unemployment – or the scaffold, or the sword, or any other malice of chance in the tangle of events. (…) It is of the embraces of despair that faith is born. Suffering brings death, but the idea brings immortality. That agony and immortality will be mingled and merged in one death. Brothers, we who die here will die in the radiance of the future. We go to a tomb flooded with the light of dawn.”

Les Misérables 5.1.5 (Trans. Norman Denny)

Michelangelo purportedly said that in a block of marble he could already see the statue he wanted to make, for he just had to chisel away the superfluous material. For Hugo, it seems like he imagined a wonderful story, but he forgot to do away with the obsolete material. Thus, at least for me, he failed to reveal the beautiful statue within, failing not only himself, but the reader as well. Oh Victor, you really did yourself short here, not to mention the reader. In that regard, I much preferred The Count of Monte Cristo by Hugo’s contemporary Alexandre Dumas.