Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) was a humanist philosopher from the French Renaissance, mostly known for his Essays, with which he established and popularized the essay as a genre. Literally meaning ‘an attempt’ (from the French essayer, ‘to try’), this new literary form was an attempt by Montaigne to put his thoughts into words. Early on in his Essays, he admits that he often felt himself incapable of successfully doing so, burdened by his own contradictory and constricting thoughts, which is why he modestly called his writings mere attempts.

“Recently I retired to my estates, determined to devote myself as far as I could to spending what little life I have left quietly and privately; it seemed to me then that the greatest favour I could do for my mind was to leave it in total idleness, caring for itself, concerned only with itself, calmly thinking of itself. I hoped it could do that more easily from then on, since with the passage of time it had grown mature and put on weight. But I find that on the contrary it bolted off like a runaway horse, taking for more trouble over itself than it ever did over anyone else; it gives birth to so many chimeras and fantastic monstrosities, one after another, without order or fitness, that, so as to contemplate at my ease their oddness and their strangeness, I began to keep a record of them, hoping in time to make my mind ashamed of itself.”

Michel de Montaigne, Essays 1.8, On idleness (trans. M.A. Screech)

At the time of writing his Essays, Montaigne was plagued by moods of melancholy, oppressed by grief and isolation. Not only did his best friend, Étienne de La Boétie, die an early death, but none of his children – except one daughter – survived beyond childhood. Writing the Essays was a way for Montaigne to deal with his melancholy, a way to exorcize the demon inside of him. Not being a professional scholar, he decided to write about himself, since it was the only subject he knew more about than anyone else. He was the first to take himself as the object of his study, examining his own nature, his habits, and his opinions. Dissecting his own virtues, vices, and feelings, Montaigne presented himself to the reader unabashedly and without shame, so that we might one day learn from him.

Introspective Musings

Montaigne did not mince words when presenting himself to the reader. At times he is even contemptuous of himself and of his own writing, as if he feels incapable of saying anything of value. It is not despite of but rather thanks to this self-doubt that his Essays are so fascinating to read. It shows his determination to think for himself and to question everything before assuming something – hence his famous motto Que sais-je? (‘What do I know?’). But his doubt and despair also express what it means to be human. In writing about his fears and flaws, he shows how we can come to terms with ours, even if there is no perfect way to deal with our imperfections.

“Whatever these futilities of mine may be, I have no intention of hiding them, any more than I would a bald and grizzled portrait of myself just because the artist had painted not a perfect face but my own. Anyway these are my humours, my opinions: I give them my own self, which may well be different tomorrow if I am initiated into some new business that changes me. I have not, nor do I desire, enough authority to be believed. I feel too badly taught to teach others.”

Michel de Montaigne, Essays 1.26, On educating children (trans. M.A. Screech)

For a large part of his life, Montaigne’s country was at war with itself, for a civil war had arisen between the Catholics and the protestants. Against the backdrop of this turmoil, Montaigne continually confronted himself with the harsh reality of life, stoically urging himself to overcome what he can and to endure what he cannot.

“Where do you think you can ever be without fuss and bother? You really should realize that nobody is in your way but yourself and that you will be following yourself about everywhere, and moaning to yourself everywhere, for there is no contentment here below except for souls like those of beasts or gods. Where can a man expect to find contentment if he is not content when he has such good cause? How many thousands of men are there whose aspirations do not exceed such circumstances as yours? Simply remould your Form: in such a matter you can do anything, whereas in face of Fortune you have no right but to endure.”

Michel de Montaigne, Essays 3.9, On vanity (trans. M.A. Screech)

Despite his efforts to get a grasp on himself, Montaigne knew it was a futile task. We must learn that in the end we are all blockheads: irrational and erratic. We simply have to admit that our human nature is too complex to comprehend, for it is contradictory, ever-changing, and most of all deeply flawed.

“Every sort of contradiction can be found in me, depending upon some twist or attribute: timid, insolent; chaste, lecherous; talkative, taciturn; tough, sickly; clever, dull; brooding, affable; lying, truthful; learned, ignorant; generous, miserly and then prodigal – I can see something of all that in myself, depending on how I gyrate; and anyone who studies himself attentively finds in himself and in his very judgement this whirring about and this discordancy. There is nothing I can say about myself as a whole simply and completely, without intermingling and admixture.”

Michel de Montaigne, Essays 2.1, On the inconstancy of our actions (trans. M.A. Screech)

In Love of Books

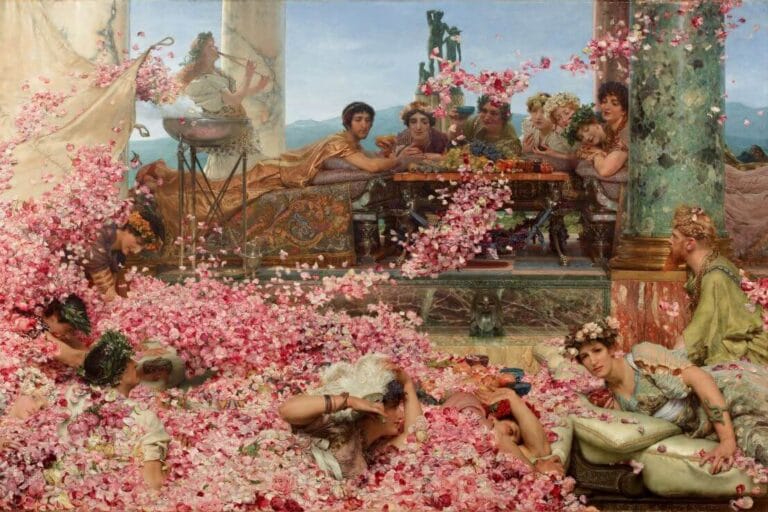

Montaigne’s love for books is evident in all of his writing. Though he presents himself modestly as a layman, it becomes clear from all his references that he is very well read. With a charming anecdote, he tells how he fell in love with literature when secretly reading Ovid’s Metamorphoses as a young boy.

“My first taste for books arose from enjoying Ovid’s Metamorphoses: when I was about seven or eight I used to sneak away from all joys to read it, especially since Latin was my mother-tongue and the Metamorphoses was the easiest book I knew and the one most suitable to my tender age. (…) I was particularly lucky at this stage to have to deal with an understanding tutor who adroitly connived at his and other similar passions: for I read in succession Virgil, Terence, Plautus, and the Italian comedies; ever seduced by the attractiveness of their subjects. Had he been mad enough to break this succession I reckon I would have left school hating books, as most French aristocrats do.”

Michel de Montaigne, Essays 1.26, On educating children (trans. M.A. Screech)

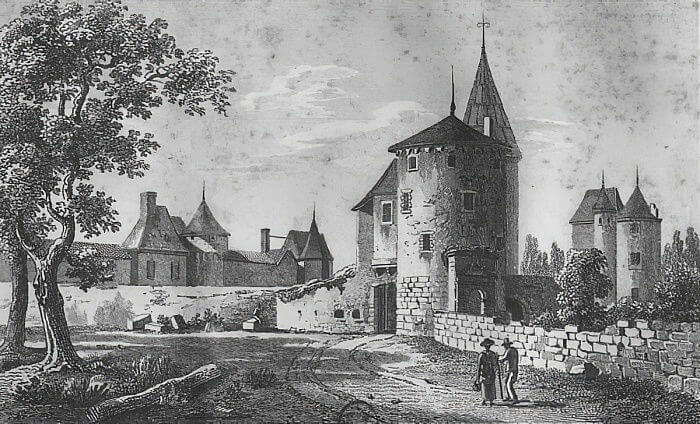

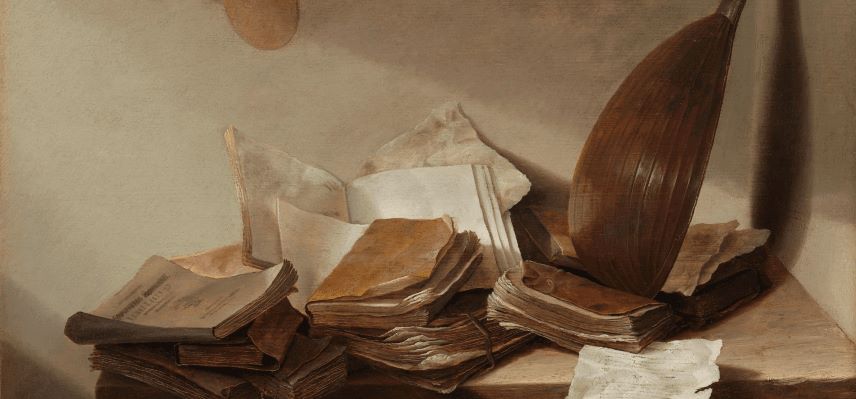

Montaigne spent most of his time in his library, which was situated in the tower of his family estate. There he would at times seek solitude or simply look for some distraction, turning over the leaves of his books without specific purpose. He had covered the beams of his library with more than sixty Greek and Latin sayings from antiquity, many of which found their way into the Essays. It is clear that Montaigne is in love with books, praising them as his best companions.

“I enjoy [books] as misers do riches: because I know I can always enjoy them whenever I please. My soul is satisfied and contented by this right of possession. In war as in peace I never travel without books. Yet days and even months on end may pass without using them. ‘I will read them soon,’ I say, ‘or tomorrow; or when I feel like it.’ Thus the time speeds by and is gone, but does me no harm; for it is impossible to describe what comfort and peace I derive from the thought that they are there beside me, to give me pleasure whenever I want, or from recognizing how much succour they bring to life. It is the best protection which I have found for our human journey and I deeply pity men of intelligence who lack it. I on the other hand can accept any sort of pastime, no matter how trifling, because I have this one which will never fail me.

Michel de Montaigne, Essays 3.3, On three kinds of social intercourse (trans. M.A. Screech)

For Montaigne, books are not just enjoyable companions, but also knowledgeable teachers. As a part of the humanist movement, Montaigne revived and drew on the ideas of classical antiquity. He was especially charmed by the poets Horace and Virgil, while for philosophy he resorted mostly to the Stoics Seneca and Cicero, whom he consulted when he for instance needed to overcome his own fear of death. Even though he was very fond of his books, he also warned against them, for we can read as much as we want, but we can only be wise with the wisdom of our own.

“We allow ourselves to lean so heavily on other men’s arms that we destroy our own force. Do I wish to fortify myself against fear of death? Then I do it at Seneca’s expense. Do I wish to fortify myself against fear of somebody else? Then I borrow from Cicero: I would have drawn it from my own resources if only I had been made to practise doing so. I have no love for such competence as is borne of and begged. Learned we may be with another man’s learning: we can only be wise with the wisdom of our own. Dionysius used to laugh at professors of grammar who did research into the and qualities of Ulysses yet knew nothing of their own; at musicians whose flutes were harmonious but not their morals; at orators whose studies led to talking about justice, not to being just.”

Michel de Montaigne, Essays 1.25, On schoolmasters’ learnings (trans. M.A. Screech)

Nearing the End

Its clear that Montaigne worked on a majority of his Essays in his later years, for he is clearly writing from the perspective of a man looking back on his life and towards his imminent death. Eventually he came to terms with his nearing end, possibly helped by Stoics (Essays 3.10, On restraining the will): “My world is over: my mould has been emptied; I belong entirely to the past; I am bound to acknowledge that and to conform my exit.” Despite nearing death, Montaigne is still able to cherish the joys of life. Even though his happiest years are now far behind him and his body is quickly decaying, it does not stop him from cherishing them in retrospect.

“Let babes look ahead, old age behind; is that not what was meant by the double face of Janus? The years can drag me along if they will, but they will have to drag me along facing backwards. While my eyes can still make reconnaissances into that beautiful season now expired, I will occasionally look back upon it. Although it has gone from my blood and veins at least I have no wish to tear the thought of it from my memory by the roots.”

Michel de Montaigne, Essays 3.5, On some lines of Virgil (trans. M.A. Screech)

As a final advice, he reminds the reader that a good life is not one filled with heroic deeds or boundless riches, because, despite status and wealth, we are still humans with human needs and feelings. Instead, he urges the reader to be pursue a rather simple life and to enjoy the pleasures life has to offer, as long as it lasts.

“It is an accomplishment, absolute and as it were God-like, to know how to enjoy our being as we ought. We seek other attributes because we do not understand the use of our own; and, having now knowledge of what is within, we sally forth outside ourselves. A fine thing to walk on stilts: for even on stilts we must ever walk with our legs! And upon the highest throne in the world, we are seated, still, upon our arses. The most beautiful of lives to my liking are those which conform to the common measure, human and ordinate, without miracles though and without rapture.”

Michel de Montaigne, Essays 3.13, On experience (trans. M.A. Screech)

Further Reading

(Wikimedida Commons)

While writing this article, I made use of the edition and translation by M.A. Screech. I can also wholeheartedly recommend Sarah Bakewell’s book How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer, as an introduction to the writings of this fascinating philosopher. And when reading his Essays, we might imagine ourselves sitting there with him in his private library, browsing through his books, lost in thought, contemplating life in peace and quiet.

“At home I slip off to my library a little more often; it is easy for me to oversee my household from there. I am above my gateway and have a view of my garden, my chicken-run, my backyard and most parts of my house. There I can turn over the leaves of this book or that, a bit at a time without order or design. Sometimes my mind wanders off, at others I walk to and fro, noting down and dictating these whims of mine.”

Michel de Montaigne, Essays 3.3, On three kinds of social intercourse (trans. M.A. Screech)