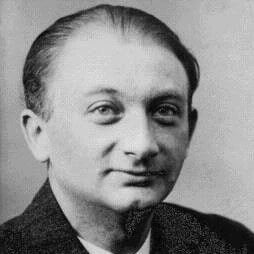

Joseph Roth (1894-1939) was an Austrian-Jewish journalist and novelist, mostly known for his novel Radetzky March. He grew up in Brody, a town on the eastern outskirts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where he learned to speak German, Yiddish, and Ukrainian. He was raised solely by his mother, since his father had disappeared before he was born. At the age of nineteen, Roth began studying German philology, first in Lemberg and later in Vienna. When World War I erupted, Roth left university and volunteered for the army. Austria-Hungary, however, was defeated and fractured into various nation-states. These events greatly influenced Roth and his writings, leaving him with a sense of homelessness, as stated by the literary critic Hoi Jensen.

(Wikimedia Commons)

“Dispossessed of his father and fatherland, a rootless Eastern European Jew on a continent gripped by nationalist fever, Roth’s self-identity was especially tenuous. To some degree, this suited him fine, at least professionally. ‘He needs a little discomfort to feel alert,’ Pim writes; ‘too much comfort is soporific.’ It also provided Roth with a certain biographical freedom, the license to invent his past as he went along. From the rubble of his past he molded new, fictional selves, adopting different personas, mannerisms and dialects. ‘He favored his imagination over reality and movement over stasis,’ Pim writes. ‘Better to dream of home, better to wander: to travel in hope, rather than to arrive, settle and be disappointed.'”

Morton Hoi Jensen, The rootless, brilliant and tragic life of Joseph Roth (WSJ)

After the defeat and the dissolution of Austria-Hungary in 1918, Roth could no longer return home, for Brody had now become a part of Poland. After wandering around for months, he at last ended up in Vienna, where he began writing for various tabloid papers. When he had finally gained some reputation as a journalist, he eventually got to work for the liberal Frankfurter Zeitung in 1923, which gave him a comfortable income and allowed him to travel through Europe as a foreign correspondent. In the same year, his first novel, The Spider’s Web, was published as a feuilleton in an Austrian newspaper. While he attained moderate success, it was not until his later works Job (1930) and Radetzky March (1932) that he achieved great acclaim as a novelist.

Radetzky March

Summary

Radetzky March is a family saga narrating the downfall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire through the lens of the Von Trottas. We follow three generations of men from this family, starting with grandfather Joseph von Trotta, who had famously – more or less by accident – saved the life of the Austro-Hungarian emperor, Franz Joseph, in the Battle of Solferino. For this act of heroism, he was elevated to nobility (translations are by Michael Hofmann).

“The Trottas were not an old family. Their founder had been ennobled following the battle of Solferino. He was a Slovene. The name of his village – Sipolje – was taken into his title. Fate had singled him out for a particular deed. He subsequently did everything he could to return himself to obscurity.”

Joseph von Trotta, who was now known as Baron Trotta von Sipolje, grew increasingly uncomfortable with his newly acquired position as a nobleman. He even asked emperor Franz Joseph in person to remove the story of his heroism from the history books, since they had dramatized his humble role on the battlefield. Because of his growing disgust of the military, he urged his son Franz to pursue an administrative career instead.

Franz von Trotta heeded his father’s wishes and ended up as a district administrator. While he himself was never allowed to pursue a military career, he recommended his own son, Carl Joseph, in turn to become a cavalry officer. Franz had forgotten his father’s distate for the army, for all that was now left of his father, the ‘hero of Solferino’, was a romanticized tale and an idealized portrait, which loomed over his grandson as a great shadow, making him feel like he could never live up to his grandfather’s reputation.

“The portrait hung in the District Commissioner’s drawing room, facing the windows, and so high up on the wall that the brow and hair were obscured in the mahogany shade of the old beamed ceiling. The grandson’s curiosity continually revolved around his grandfather’s dim figure and extinguished flame. (…) Every year, in the summer holidays, the grandson’s silent conversations with his grandfather were resumed. The dead man gave nothing away. The boy learned nothing from him. From year to year, the painting seemed to become dimmer and more otherworldly, as though the hero of Solferino had to die all over again, as though he was gradually taking back all memory of himself, and as though there would one day come a time in which an empty canvas would stare down from the black frame upon his progeny with an even more profound discretion than the portrait.”

Oppressed by his own shortcomings and overshadowed by his grandfather’s fame, Carl Joseph struggled to achieve anything noteworthy as a cavalry officer. Like most of his fellow officers during peace-time, he wasted his time and money on women, wine, and gambling. After being indirectly involved in the death of his friend Max Demant, Carl Joseph was transferred from the prestigious Uhlans to the less reputable Jägers, stationed on the easternmost outskirts of the empire, next to the border with Russia. Now he was disconnected from civilization and he entered a desolate world devoid of any comfort.

“Any strangers who came to this part of the world were slowly but irresistibly doomed. No one was a match for the swamp. No one could stand up to the border. At that time, the important people in Vienna and Petersburg were already making their preparations for the Great War. The people on the border felt it coming before anyone else did (…). And in the tedious swampy remoteness of the garrison, from time to time an officer would fall prey to despair, cards, debts, and sinister contacts. The cemeteries of the border garrisons held the bodies of many weak young men.”

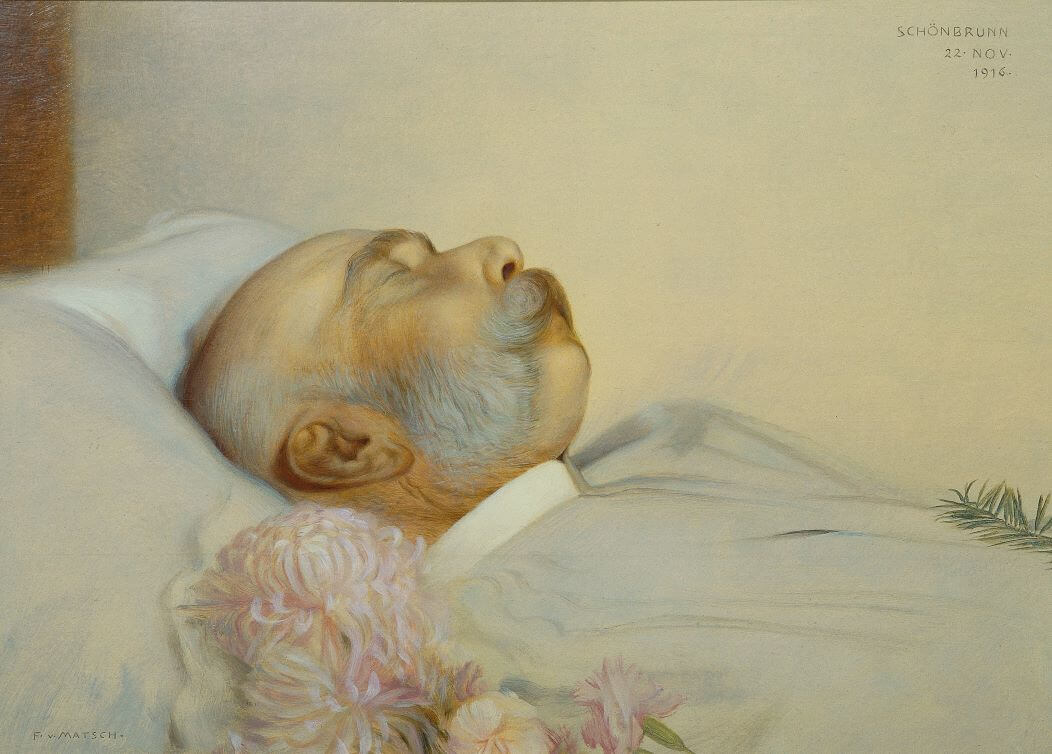

After a number of scandals, including gambling debts, a secret affair, and the execution of several civilians during an industrial strike, Carl Joseph died without honour during the opening days of World War I, unable to emulate his grandfather’s glory on the battlefield. He was shot through the head with two buckets of water in his hands. His father and the emperor, two figures of the old world, would die soon after. Their deaths marked the end of an era: the Austro-Hungarian Empire would soon belong wholly to the past. The First World War would shake everything up. But it no longer mattered to Franz von Trotta, the ever loyal district administrator, for he had not just lost his son, but also everything he had ever believed in. From now on, the world would never be the same.

“What did Herr von Trotta care about the hundred thousand dead who had since followed his son? What did he care about the hasty and confused decision taken by the people above him, that were issued on a weekly basis? And what did he care about the end of the world, which he could now see approaching with even greater clarity than once the prophetic Chojnicki could? His son was dead. His job was over. His world had ended.”

Themes

The great theme of Radetzky March is the downfall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The book exudes a wistful and enchanting atmosphere full of nostalgia. Roth sketches this period so lovingly in Radetzky March that it almost makes you long for that old world, the world before World War I: a slow, hierarchical, bureaucratic world, where you knew what to expect, but that had long since ceased to function and where there was little room for change. Just one year after publishing the novel, in 1933, Hitler got to power in Germany and Roth fled the country. The rising tensions in Europe and the events ensuing World War I likely contributed to Roth’s longing for the past. Despite all the flaws of Austria-Hungary, Roth could not hide his nostalgia for this old world in Radetzky March, as he admits in one of his letters.

“My strongest experience was the War and the destruction of my fatherland, the only one I ever had, the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.”

Conclusion

Reading Radetzky March by Joseph Roth was an absolute pleasure. The language in the novel is incredibly rich and the sentiment of the period is vividly evoked – at least it was in the impeccable Dutch translation by Els Snick that I read. It is written so poetically and lovingly that I can recommend everyone to give the book a try, if only for its lyric quality- even if you have no interest in or prior knowledge of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It would not surprise me if I would one day come back to this book, back to the old world that seems but a relic from a distant past, and back to an age of innocence before the atrocities of the Great War.

“They had been born in peacetime and had become officers by dint of peaceful manoeuvres and exercises. At the time they were still unaware that each of them, without exception, would have an assignation with Death within a couple of years. At the time none of them was able to hear the machinery of the great hidden mills that were already beginning to grind out the Great War.”