Ceterum censeo Carthaginem delendam esse. It was with this line that the Roman senator Cato the Elder famously ended all of his speeches. With it, he hammered home the message that Rome and Carthage could not coexist. There was only room for one superpower in the Mediterranean, he seemed to imply. The Punic Wars that ensued would seal the fate of this Carthaginian Empire that once dominated the Mediterranean, an empire that at its height stretched from Southern Spain to modern-day Libya, flourishing from its international trading networks, its seafaring skills, and its unique system of government. If it was not for a twist of fate, it might have been the Carthaginian Empire rather than the Roman Empire that steered the course of history in Western Europe.

Foundation: Queen Dido

The city of Carthage is generally assumed to have been founded in the 9th century BC, by Phoenician colonists from the city of Tyre, in modern-day Lebanon. According to its foundation myth, it was the exiled princess Dido, also known as Elissa, who led this group of settlers to their new lands. After her husband had been killed by her treacherous brother Pygmalion, Dido and her followers decided to secretly flee the city in order to escape his tyrannic reign. Eventually arriving somewhere on the coast of North Africa, around modern-day Tunisia, some traditions recount them meeting the Berber king Iarbas, who mockingly offered her as much land as one ox-hide could cover. Cunning as she was, the princess cut the hide into thin strips with which encircled the hill of Byrsa, which would later become the city’s acropolis. And thus Carthage was founded.

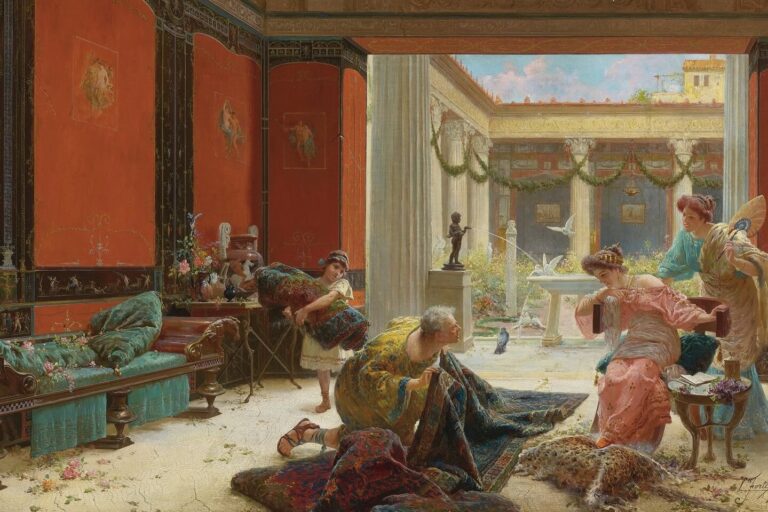

Since few Punic writings have survived, we almost exclusively rely on accounts of Carthage’s enemies – so too with its foundation myth. After all, its most famous account is that of the Roman poet Vergil, who in his Aeneid recounts the Trojan prince Aeneas fleeing from his fatherland after the sack of Troy, ordered by the gods to found a new city in far-away lands – not so different from Dido. When Aeneas arrived at the shores of North Africa, ship-wrecked and disoriented, exploring the lands close to the shore, he stumbled upon a breathtaking sight: the bustling city of Carthage.

“And soon they climbed the hill that looms high over the city, and looks down from above on the towers that face it. Aeneas marvels at the mass of buildings, once huts, marvels at the gates, the noise, the paved roads. The eager Tyrians are busy, some building walls, and raising the citadel, rolling up stones by hand, some choosing the site for a house, and marking a furrow: they make magistrates and laws, and a sacred senate: here some are digging a harbour: others lay down the deep foundations of a theatre, and carve huge columns from the cliff, tall adornments for the future stage.”

Vergil, Aeneid 1.419-429 (trans. A.S. Kline)

Besides legitimizing Rome’s glory by providing it with a legendary past, Vergil also attempts to explain the eternal enmity between Carthage and Rome. He does so by interweaving the fates of the Trojan prince and the Tyrian princess. It starts out almost like a fairy tale, but it ends in burning hatred. With a little help of the gods, the two are introduced to each other. Dido shows her guest the bustling city and Aeneas tells her about the fate of Troy and of his travels. When they go out hunting and amidst a thunderstorm take refuge in a cave, they finally succumb to love.

But alas, it was not to last. Commanded by the supreme god Jupiter, Aeneas is urged to continue his mission to found a new city, and so he sets sail and leaves his beloved Dido. Raging and inconsolable, she erects a funeral pyre on which she then proceeds to kill herself, but not before she cursed Aeneas and his people: that they may be in eternal strife with Carthage and that one of her people may one day avenge her. Of course, Vergil has none other in mind than Hannibal himself.

“Let there be no love or treaties between our peoples. Rise, some unknown avenger, from my dust, who will pursue the Trojan colonists with fire and sword, now, or in time to come, whenever the strength is granted him. I pray that shore be opposed to shore, water to wave, weapon to weapon: let them fight, them and their descendants.”

Vergil, Aeneid 4.624-629 (trans. A.S. Kline)

Eternal Strife: The Punic Wars

At the time that Rome and Carthage first came into conflict with each other, in the third century BC, Carthage was a maritime empire with a superior navy, dominating the western Mediterranean and controlling the trading routes. Rome, however, was expanding mostly over land, conquering the whole of the Italian Peninsula. When they crossed the strait to the island of Sicily, which was then largely under control of Carthage, the First Punic War erupted. The maritime hegemony of Carthage provided them with a great advantage, enabling them to supply and reinforce their cities by sea. When the Romans, however, got their hands on a Carthaginian ship, they copied its design, upgraded it with a corvus (litt. ‘crow’, a drawbridge to board an enemy ship), and were thus at last able to challenge Carthage’s navy. Combined with their superiority on land, they eventually managed to get out on top. Carthage had to concede Sicily and pay hefty war reparations.

Miraculously, Carthage flourished after the war. They expanded into Spain, under the leadership of Hamilcar Barca, where they above all other things profited from the silver-mines, which enabled them not only to pay the war reparations imposed by the Romans, but also to rebuild a strong army. This expansion into the Iberian Peninsula was led by Hamilcar Barca, the father of Carthage’s greatest general: Hanibal Barca. The story goes that, before Hamilcar set off to Spain, he made his son, who then was just a boy, swear that he would forever be an enemy of Rome.

“It is said moreover that when Hannibal, then about nine years old, was childishly teasing his father Hamilcar to take him with him into Spain, his father, who had finished the African war and was sacrificing, before crossing over with his army, led the boy up to the altar and made him touch the offerings and bind himself with an oath that so soon as he should be able he would be the declared enemy of the Roman People.”

Livy, Ab Urbe Condita 21.1.4 (trans. William Heinemann)

Using their bases in Spain, Hannibal set out for a surprise attack on Rome, setting out from Carthage, crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, traversing the Iberian and Gallic mainlands, and miraculously crossing the alps. It would be a stretch to say that he caught the Romans unawares. Hannibal openly declared war when he attacked the Iberian city of Saguntum, an declared ally of Rome, and Rome was informed about Hannibal’s campaigns. But they simple did not think it possible for someone to traverse the narrow, steep, and slippery mountain ridges of the Alps.

“When the Alps, the other side of which was in Italy, were in full sight, were they halting now, as though exhausted, at the very gates of their enemies? What else did they think that the Alps were but high mountains? They might fancy them higher than the ranges of the Pyrenees; but surely no lands touched the skies or were impassable to man.”

Livy, Ab Urbe Condita 21.30.5- 7 (trans. William Heinemann)

In Italy, Hannibal won every battle against the Romans. In great distress, the Romans appointed Fabius Maximus as dictator, bestowing upon him the full power of the state to deal with this crisis that threatened the very existence of Rome. Fabius adopted a method of delaying a head-on confrontation with Hannibal, opting rather to target Carthaginian supply lines and to accept only smaller engagements on favorable ground. Hence, he was given the agnomen (‘nickname’) Cunctator (‘the delayor’). The Romans successfully avoided a full-blown defeat, but when Fabius laid down his dictatorship, the new consuls Varro and Paullus abolished this strategy and headed for a direct confrontation at a place near Cannae, in southern Italy. Hannibal convincingly won the battle in what would be known as the most horrific and humiliating defeat in Rome’s history, with an estimated 67.500 Romans killed and captured. And if it was not for Hannibal’s indecision to march on Rome, this devastating defeat could have ensured the downfall of Rome.

“Hannibal’s officers crowded round him with congratulations on his victory. The others all advised him, now that he had brought so great a war to a conclusion, to repose himself and to allow his weary soldiers to repose for the remainder of that day and the following night. But Maharbal, the commander of the cavalry, held that no time should be lost: (…) “In very truth the gods bestow not on the same man all their gifts; you know how to gain a victory, Hannibal: you know not how to use one.” That day’s delay is generally believed to have saved the City and the empire.”

Livy, Ab Urbe Condita 22.51 .1-4 (trans. William Heinemann)

Aftermath: The Fall of Carthage

Instead of Rome, it was Carthage that was doomed to fall. Soon after the Battle of Cannae, the Roman general Scipio had invaded the Carthaginian homeland and Hannibal was recalled. At the battle of Zama, Scipio decisively defeated Hannibal and earned himself the agnomen Africanus. The Romans again imposed onerous terms for peace on Carthage, demanding from them to concede all territory outside Africa, to pay a massive indemnity over the next fifty years, to possess no more than ten warships, and to only wage war with the permission of Rome. When they were attacked by the Numidians, they could not but defend themselves and thus break the peace treaty.

It would be Scipio Aemilianus, the grandson of the Scipio Africanus, who led the siege against Carthage. Fighting with tooth and nail, the Carthaginians held out for a surprisingly long time. After three years, the Romans finally managed to sack the city. They allegedly killed everyone they encountered and burned the whole city to the ground, including the archives of Carthage, which is why virtually no Punic writings have been handed down to us. The Romans were merciless and unforgiving in their conquest of Carthage, ensuring that their archenemy would never again rise from its ashes. Nonetheless, the Greek historian Polybius records Scipio Aemilianus weeping at the sight of Carthage burning while citing from Homer’s Iliad, realizing it is the fate of every civilization, as it is the fate of mankind, to come into being, to flourish, and to perish into oblivion.

“Scipio, when he looked upon the city as it was utterly perishing and in the last throes of its complete destruction, is said to have shed tears and wept openly for his enemies. After being wrapped in thought for long, and realizing that all cities, nations, and authorities must, like men, meet their doom; that this happened to Ilium, once a prosperous city, to the empires of Assyria, Media, and Persia, the greatest of their time, and to Macedonia itself, the brilliance of which was so recent, either deliberately or the verses escaping him, he said:

A day will come when sacred Troy shall perish,

And Priam and his people shall be slainAnd when Polybius speaking with freedom to him, for he was his teacher, asked him what he meant by the words, they say that without any attempt at concealment he named his own country, for which he feared when he reflected on the fate of all things human.”

Polybius, The Histories 38.22 (trans. W.R. Paton)

Further Reading

Richard Miles’ Carthage Must Be Destroyed seems to be the most recent comprehensive study of Carthage and thus the best introduction to the subject. In addition, I can also recommend his Channel 4 documentary Carthage: The Roman Holocaust. As for primary sources, Polybius’ Histories and Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita are our main sources, of which the former is generally thought to be more reliable. As for podcasts, the brilliant Fall of Civilizations has made an episode on Carthage, which can also be viewed as a documentary on YouTube here. And the marvelous BBC Four radio program In Our Time also has episodes on Hannibal and Carthage’s Destruction.