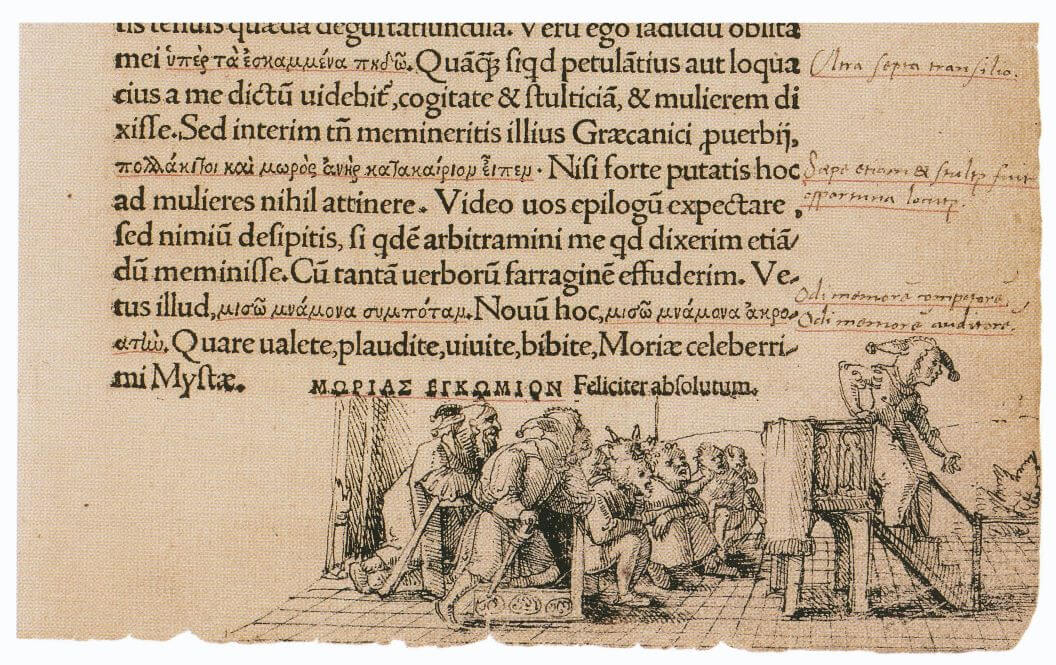

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (c. 1466-1563) was a Christian humanist philosopher from the Netherlands, now considered to be one of the most influential thinkers of the European Renaissance. As a provocateur of contemporary standards, he was mostly known for the countless polemic letters he wrote to statesmen, humanists, and theologians. But Erasmus was much more than just a provocateur. To sum it up: he was a humanist, philologist, essayist, theologian, biblical scholar, translator, editor, and a satirist. Amongst other things, he edited and collected a myriad of proverbs from classical antiquity in his Adages, he edited and translated the New Testament from Greek to Latin, and he wrote the satire The Praise of Folly, which will be today’s topic. While the satire is now counted amongst his best writings, Erasmus regarded it merely as a minor work. In a prefatory letter to his friend Thomas More, he claims that he wrote it mostly to entertain himself.

“During my recent journey back from Italy to England, not wishing to waste all the time I was obliged to be on horseback on ‘idle gossip’ and small talk, I preferred to spend (…) it thinking over some topic connected with our common interest or else enjoying the recollection of the friends, as learned as they are delightful, whom I had left here. You were amongst the first of these to spring to mind, my dear More. I have always enjoyed my memories of you when we have been parted from each other as much as your company when we were together, and I swear that nothing has brought me more pleasure in life than companionship like yours. And so since I felt that there must be something I could do about this and the time was hardly suitable for serious meditation, I decided to amuse myself with praise of folly.”

Erasmus, Prefatory Letter to The Praise of Folly (trans. Betty Radice)

Note that Erasmus wrote the work with his friend Thomas More in mind. In fact, it was More’s name that inspired Erasmus to write it, he says, because it so closely resembled the Greek word for folly (moria). Despite Erasmus’ lighthearted motivations, The Praise of Folly is more substantial and learned than the title would suggest. It is packed with allusions to biblical, scholastic, and classical texts, so you would have to be extremely well-versed in theology and classical philology to get just a grasp of what Erasmus is aiming at. It enabled Erasmus to add implicit, indirect, and concealed criticism without explicitly stating things forbidden by the church. For, most of all, The Praise of Folly was a critique of the Catholic Church, the clergy, and of pedantic theologians.

The Praise of Folly

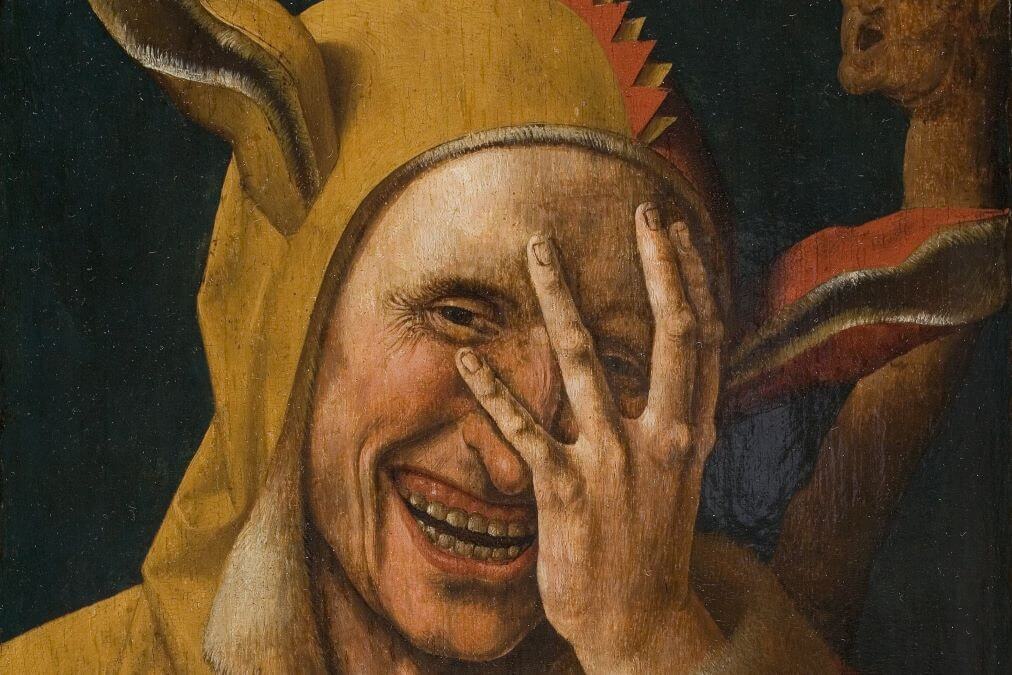

In The Praise of Folly, it is Folly itself who is speaking. In the style of the Greek satirist Lucian, Folly praises herself for all the gifts she bestows on mankind. Accompanied by her attendants Lethe (Forgetfulness), Misoponia (Idleness), Hedone (Pleasure), and others, she dismisses all prejudices against her and explains why it is in fact not Wisdom but Folly that guides men to happiness.

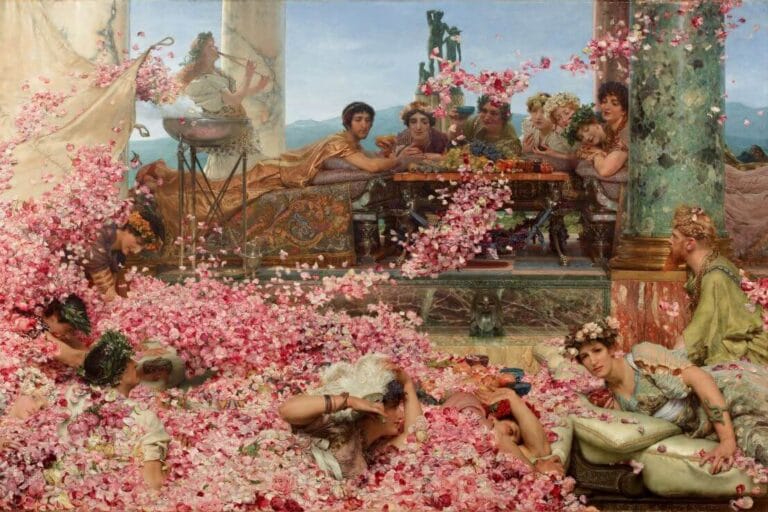

Firstly, Folly argues that she governs all parts of life. Without Folly, a man would never ‘offer his neck to the halter of matrimony’. Without Folly, a woman would never ‘agree to take a husband if she knew or thought about the pains and dangers of childbirth and the trouble of bringing up children’. Without Folly, friendships and alliances would not even exist, for it is Folly who provides us with flattery, hypocrisy, and illusions about the other, thus enabling us to engage with others. Without the Self-Love (Philautia) granted by Folly, no one would undertake anything of value, for one would not deem oneself worthy of the attempt. It is for these reasons that people call childhood the happiest age of man, because a child is not yet burdened by wisdom and wit: ‘as soon as the young grow up and develop the sort of mature sense which comes through experience and education, the bloom of youthful beauty begins to fade at once, enthusiasm wanes, gaiety cools down, and energy slackens.’ As one grows old, Forgetfulness (Lethe) helps us to again forget our cares, introducing a second childhood. Thus, Folly enables people to live in blissful ignorance.

“What would this life be, or would it seem worth calling life at all, if its pleasure was taken away? (…) I’d just like them to tell me if there’s any part of life which isn’t dreary, unpleasant, graceless, stupid, and tedious unless you add pleasure, the seasoning of folly. I’ve proof enough in Sophocles, a poet who can never adequately praised, who pays me a really splendid tribute in the line: ‘For ignorance provides the happiest life.’”

Erasmus, The Praise of Folly (trans. Betty Radice)

Secondly, Folly ridicules people who are usually admired for their wisdom: scholars – especially theologians –, clergy, and rulers. They are deemed respectable, but unjustifiably so. Lawyers use incomprehensible language ‘to make their profession seem the most difficult’, philosophers claim to know everything while they cannot even ‘see the ditch or stone lying in their path’, and theologians call anyone a heretic who does not agree with them. Princes, cardinals, and bishops are deemed to act in the public interest, but they truly are only interested in their own pleasure. So, in reality, even learned men, who are deemed prudent, are all governed by Folly rather than Wisdom.

“But it’s sad, people say, to be deceived. Not at all, it’s far sadder not to be deceived. They’re quite wrong if they think man’s happiness depends on actual facts; it depends on his opinions. For human affairs are so complex and obscure that nothing can be known of them for certain, as has been rightly stated by my Academicians, the least assuming of the philosophers. Alternatively, if anything can be known, more often than not it is something which interferes with the pleasure of life. Finally, man’s mind is so formed that it is far more susceptible to falsehood than to truth. (…) The fools are better off, first because their happiness costs them so little, in fact only a grain of persuasion, secondly because they share their enjoyment of it with the majority of men. Indeed, no benefit gives pleasure unless it is enjoyed in company.”

Erasmus, The Praise of Folly (trans. Betty Radice)

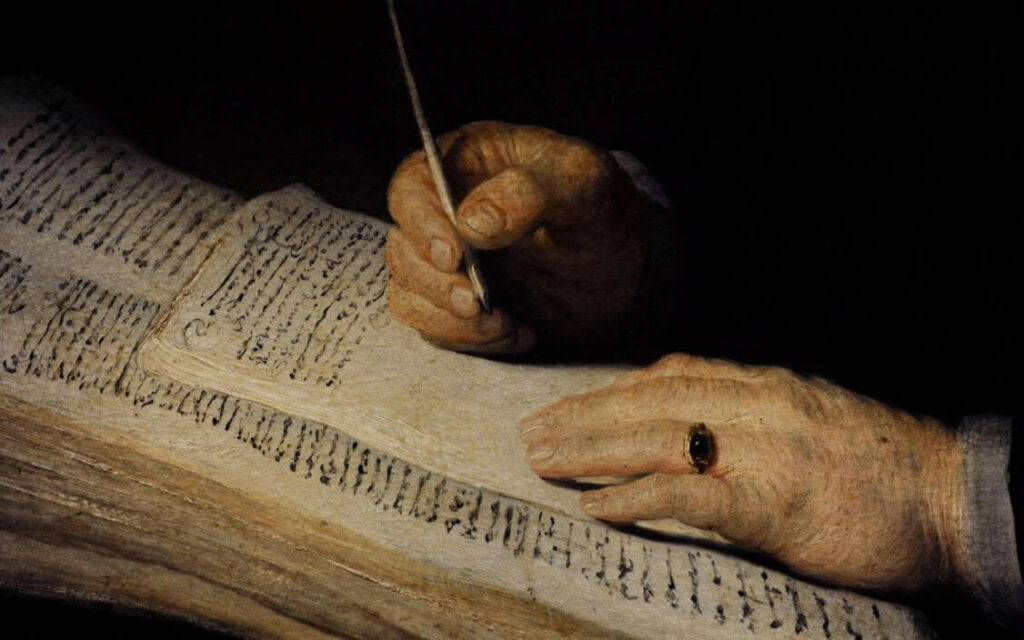

Folly’s critique of the impoverished writer is especially charming, because it is clear that Erasmus had himself in mind. While the fool puts down whatever he fancies, the wise is never satisfied.

“People who use their erudition to write for a learned minority (…) are to be pitied for their continuous self-torture. They add, change, remove, lay aide, take up, rephrase, show to their friends, keep for nine years, and are never satisfied. And their futile reward, a word of praise from a handful of people, they win at such a cost – so many late nights, such loss of sleep, sweetest of all things, and so much sweat and anguish.”

Erasmus, The Praise of Folly (trans. Betty Radice)

Thirdly, Folly even goes so far as to call Christianity itself foolish. First of all, Folly argues, the Holy Scripture is full of contradictions, which in turn are interpreted in contradictory ways. For theologians ‘pick out four or five words from different contexts, and if necessary even distort their meaning to suit their purpose.’ And was it not God who in the Garden of Eden forbade Adam and Eve to eat from the tree of knowledge? Secondly, the weak and foolish take the greatest delight in the sacred. Thirdly, the founders of Christianity were lovers of simplicity. And fourthly, Christians appear foolish because of their excessive piety. Surely one must be crazy to shun all pleasure in favour of an ascetic life full of fear and self-denial. According to Folly, that is pure madness.

“To sum up (or I shall be pursuing the infinite), it is quite clear that the Christian religion has a kind of kinship with folly in some form, though it has none at all with wisdom. If you want proofs of this, first consider the fact that the very young and the very old, women and simpletons are the people who take the greatest delight in sacred and holy things, and are therefore always found nearest the altars, led there doubtless solely by their natural instinct. Secondly, you can see how the first founders of the faith were great lovers of simplicity and bitter enemies of learning. Finally, the biggest fools of all appear to be those who have once been wholly possessed by zeal for Christian piety. They squander their possessions, ignore insults, submit to being cheated, make no distinction between friends and enemies, shun pleasure, sustain themselves on fasting, vigils, tears, toils, and humiliations, scorn life, and desire only death – in short, they seem to be dead to any normal feelings, as if their spirit dwelt elsewhere than in their body. What else can that be but madness?”

Erasmus, The Praise of Folly (trans. Betty Radice)

Conclusion

The Praise of Folly was way more readable than I anticipated, thanks to both Erasmus’ wit and the elaborate notes in my edition. Erasmus’ critique of the church might not resonate as much today, but the Folly and hypocrisy he ridiculed are still very much present in modern-day society. In a post-truth era, where opinions are deemed more important than facts, it is not that foolish to say that Folly reigns supreme in our time. Should we too give in to Folly, especially if our illusions make life bearable, if flattery, hypocrisy, and dishonesty make dealing with others easier? It is striking that it is often the fool that rolls in money, the fool that is put charge of state affairs, the fool that lives in comfort and admiration. It seems unfair, Erasmus seems to imply.

“Fools, on the other hand, are rolling in money and are put in charge of affairs of state; they flourish, in short, in every way. (…) If he wants to get rich, how much money can he make in business if he lets wisdom be his guide, if he recoils from perjury, blushes if he’s caught telling a lie, and takes the slightest notice of those niggling scruples wise men have about thieving and usury? (…) If you’re after pleasure, then women are wholeheartedly for the fools, and flee in horror from a wise man as from a scorpion. Finally, all who look for a bit of gaiety and fun in life keep their doors firmly shut against the wise, more than anything – they’ll open it to any other living creature first. In short, wherever you turn, to pontiff or prince, judge or official, friend or foe, high or low, you’ll find nothing can be achieved without money; and as the wise man despises money, it takes good care to keep out of his way.”

Erasmus, The Praise of Folly (trans. Betty Radice)

While Erasmus does not seem to regret his pursuit of Wisdom, for he remained intellectually independent throughout his life, it was not without sacrifice. For it is the fate of the wise man to live an arduous life, one lived in poverty and scorn, filled not with sensual delights but with pleasures of the mind. Still, it is worth pursuing. As Hesiod says, ‘the road to virtue is long and steep, and rough at first’ (Works and Days 290-291). However, you cannot but think that Erasmus must have wondered what it would be like to live a normal life, one of Folly rather than Wisdom.

“Let’s now compare the lot of a wise man with that of this clown. Imagine some paragon of wisdom to set up against him, a man who has frittered away all his boyhood and youth in acquiring learning, has lost the happiest part of his life in endless wakeful nights, toil, and care, and never tastes a drop of pleasure even in what’s left to him. He’s always thrifty, impoverished, miserable, grumpy, harsh, and unjust to himself, disagreeable and unpopular with his fellows, pale and thin, sickly and blear-eyed, prematurely white-haired and senile, worn-out and dying before his time. Though what difference does it make when a man like that does die? He’s never been alive. There you have a splendid picture of a wise man.”

Erasmus, The Praise of Folly (trans. Betty Radice)