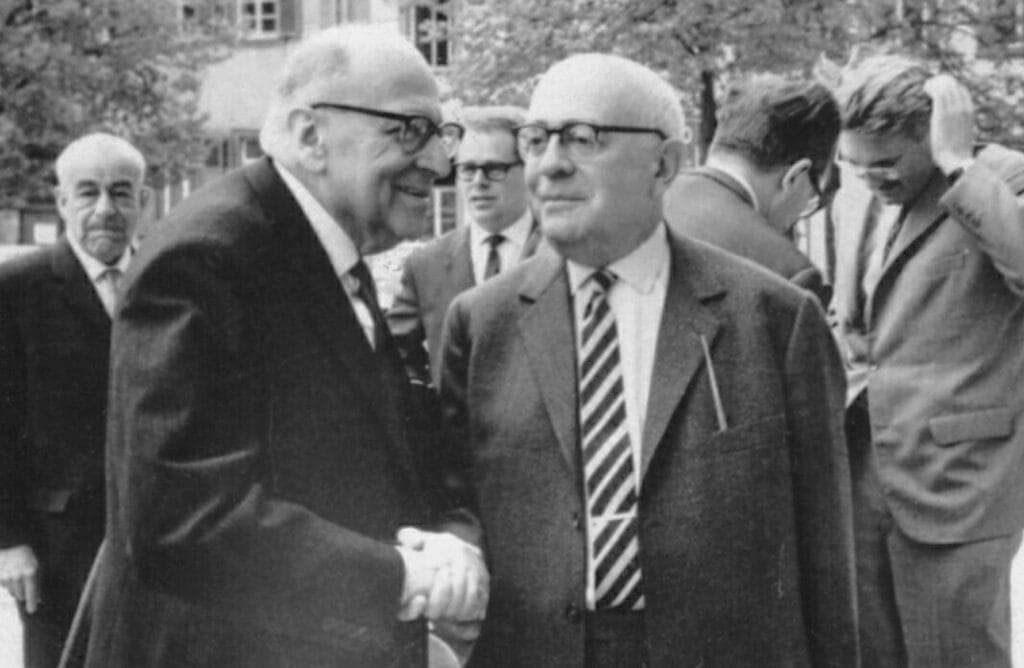

‘Enlightenment, understood in the widest sense as the advance of thought, has always aimed at liberating human beings from fear and installing them as masters. Yet the wholly enlightened earth radiates under the sign of disaster triumphant’. This is how the Frankfurt School philosophers Horkheimer and Adorno begin their Dialectic of Enlightenment, a critique of the Kantian ideal that ‘Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity’. For, they conclude, the once so promising ideal of the Enlightenment has never been realized.

“Enlightenment, understood in the widest sense as the advance of thought, has always aimed at liberating human beings from fear and installing them as masters. Yet the wholly enlightened earth is radiant with triumphant calamity. Enlightenment’s program was the disenchantment of the world. (…) What human beings seek to learn from nature is how to use it to dominate wholly both it and human beings. Nothing else counts. Ruthless toward itself, the Enlightenment has eradicated the last remnant of its own self-awareness.”

Horkheimer & Adorno, The Dialectic of Enlightenemen: 1-2.

In fact, Horkheimer and Adorno saw the rise of fascism, Stalinism, and mass consumer capitalism not as a deviation from the otherwise cherished ideal, but thought this to be the consequence of the beliefs the Enlightenment entailed. They argued that these beliefs had led not to a more free, just, and egalitarian society, but rather had proved to give way to new forms of domination and societal decline. With the rise of Nazism in Germany, Horkheimer and Adorno were forced to flee to the United States, experiencing first-hand what they would later call the regression of reason.

A Critique of the Enlightenment

The Enlightenment was supposed to be an antidote against myth, religion and injustice, but fascism showed that these ideals were far from realized. Rather, people showed to be susceptible to demagogues and were far from liberated by reason. In their Dialectic of Enlightenment, Horkheimer and Adorno attempt to explain why the Enlightenment has not realized all of its ideals. The work is best explained through three central concepts: the first concept is mythology, the second one is domination, and the third and final notion is that of the culture industry.

Myth

First off, let me touch upon the aspect of myth. ‘Myth is enlightenment, and enlightenment reverts to mythology’, the 1944 preface states. Already in antiquity, philosophers tried to rationalize and demythologize the order of nature. The change of seasons was no longer instigated by the goddess Demeter, streams were no longer seen as the dwellings of river deities, and the Olympic gods were even assimilated to the Platonic Forms. So already far before the Enlightenment, there was a strong tendency to intellectualize and rationalize the mythological word into a natural world that could hold no further mysteries to pure reason. Everything was thought to be intelligible by sound logic.

But paradoxically Adorno and Horkheimer saw myth both as a victim and as a product of the Enlightenment. In their own words: ‘Myth is already enlightenment, and enlightenment reverts to mythology.’ While the Enlightenment aimed at getting rid of superstitious believes, in failing to make all things intelligible by use of scientific and secular reason, it was responsible for a new and even greater fear: the fear of the unintelligible. Instead of the gods of old, the Enlightenment turned to their new self-made gods: to positivism, empiricism, and scientism. Thus, it has taken on the exact thing it promised to abolish. The demythologization of nature, the annulling of what they deemed as ‘animist superstition’, eventually led to our desire for absolute control over ourselves, others, and the world around us, which Horkheimer and Adorno called domination.

Domination

Secondly then, I will discuss the concept of domination. The idea of the enlightenment that nothing was out of reach for reason, that nothing was ungraspable, at the same time brought mankind a form of alienation from nature. Man, with his newly acquired power over nature, changed his attitude to the world. As Horkheimer and Adorno say, ‘he knows [the things] to the extent that he can manipulate them’. Man had adopted an instrumental use of reason, using it only in order to attain total domination. This domination is threefold: it is the domination of external nature by human beings (subjugation of nature), the domination of the nature within human beings (psychological repression), and the domination of other human beings (social exploitation).

These forms of dominations permeate and radically change the way we live together. In short, people subjugate nature, repress their needs and desires, and exploit one another by following the principle of exchange. The transactional and positivist attitude alienates us not only from others, but also from ourselves. Our capitalist societies furthermore feed these forms of domination, while itself also resembling domination. Capitalism is namely only ‘interested’ in things insofar it can make us of them, and – more importantly – it disregards and abolishes everything that is incommensurable and that bears no quantifiable that can be extracted.

The Culture Industry

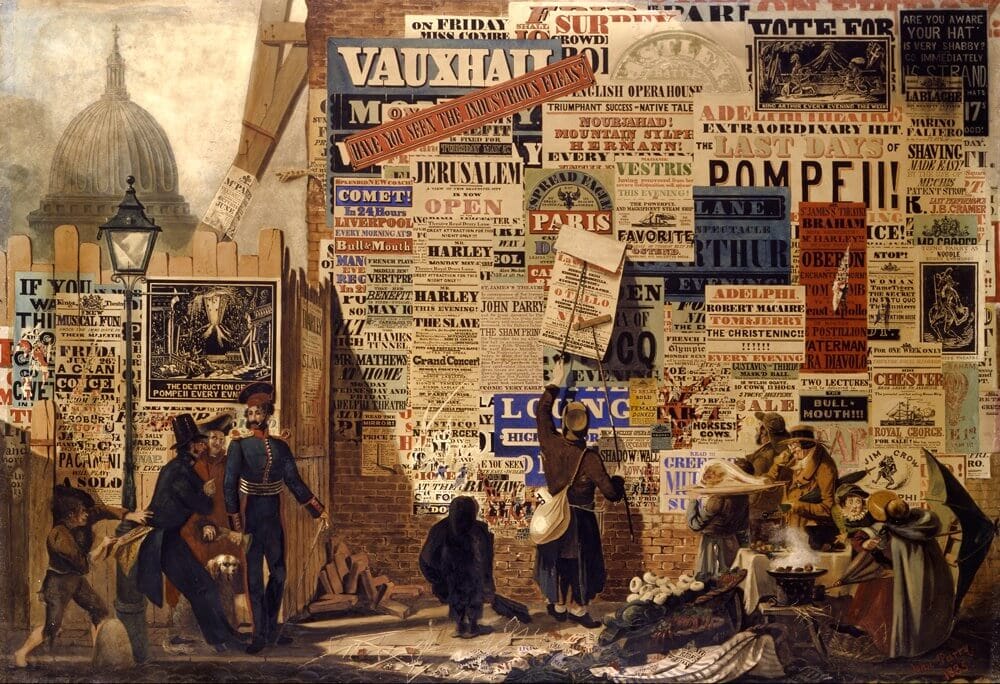

Thirdly then, I shall examine the relation between domination and capitalism further by discussing Horkheimer and Adorno’s concept of the so called ‘culture industry’. This is the idea that the mass industry of popular culture is a manifestation and a source of domination within capitalist societies. Cultural ‘products’ like film or radio more often than not have become mere forms of entertainment. Culture or art, for that matter, no longer seems to progress, no longer seems to push the boundaries. Rather, ‘culture today is infecting everything with sameness’. Adorno takes music as an example. There is mass produced popular music and classical music. The first will be omnipresent (in supermarkets, public space, school) and simplistic, making it accessible but also void, distracting the audience while stimulating them not to think. The second (i.e. serious music) will be scarcely heard in public, as it is challenging and demands active listening, but for that reason it would also invite the listener to be critical.

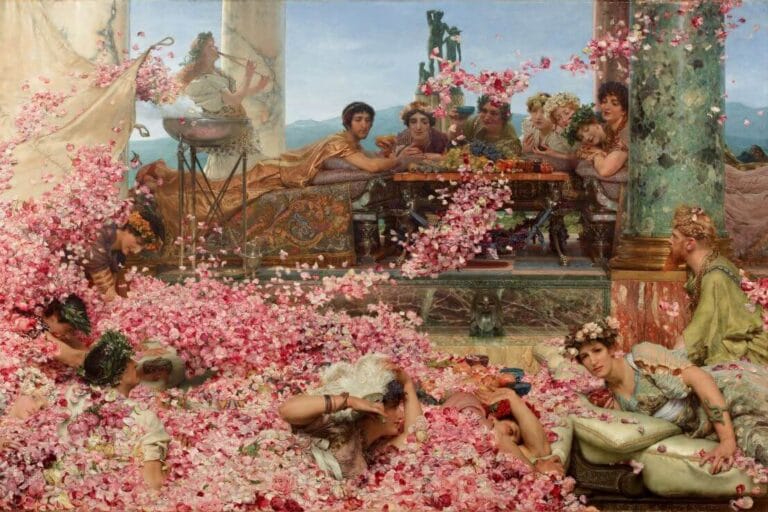

This mass produced form of entertainment allows the consumer to cope with his labour-induced fatigue. To him, it might seem like the ultimate form of freedom, as he chooses this entertainment of his own volition, in reality he is anything but free. For in fact this form of escapism sedates the consumer into a state of passivism, stimulating him not to reflect on his dire socio-economic situation and thus preventing them from revolting. And behind the curtains, it is the wealthy capitalist who is setting this production in motion, who through his apprehension of technology is the source of domination over nature and over other human beings. Thus, Horkheimer and Adorno pointed out how popular culture robs the masses of critical thinking, by distracting them from their societal struggles with accessible but shallow distractions like pop music. The people are enslaved without realizing it. And it is not like these forms of entertainment did not exist before the culture industry, Horkheimer and Adorno willingly admit. It is just that the modern industrial society has enabled the wealthy to exploit these tendencies in spectacular fashion.

This phenomenon of the culture industry is reinforced by advertising, according to Horkheimer and Adorno. ‘It strengthens the bond which shackles consumers to the big combines’. Advertising has even got a whole new, positive connotation. Nowadays, advertising is like a ‘seal of approvement’: something becomes suspect when it does not bear its mark. Its influence even reaches so far that it effects not only the consumer’s shopping habits, but also his social behaviour. Horkheimer and Adorno observe that even the most intimate interactions are unconsciously mirroring or reifying the model that the culture industry present. The culture industry has gotten so much power over society that consumers imitate their advertising even though they recognize it as false. This is the triumph of the culture industry, they conclude.

Horkheimer and Adorno wrote the Dialectic of Enlightenment in 1947. Almost a century later, here we are. A world that is full of advertising and misinformation, in which consumerism and escapism are encouraged, and in which people are willingly misled by populist politicians as if elections were just another talent show. If only mankind would regain some of its critical thinking. In our post-truth era, where opinions are deemed more important than facts, it is not that foolish to say that Folly reigns supreme in our time, to paraphrase Erasmus’ The Praise of Folly.

Bibliography

Horkheimer, M., Schmid Noerr, G., & Adorno, T. W. (2002). Dialectic of Enlightenment. Stanford University Press.

Leezenberg, M., & De Vries, G. (2019). ‘Critical Theory’. In History and Philosophy of the Humanities: An Introduction (pp. 209-236). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Rich, J. (2014). ‘The Critique of Enlightenment and the Culture Industry’. In Adorno: A critical guide (pp. 9-33). Penrith England: Humanities-Ebooks.

Zuidervaart, L. (2015). ‘Theodor W. Adorno’, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/adorno/