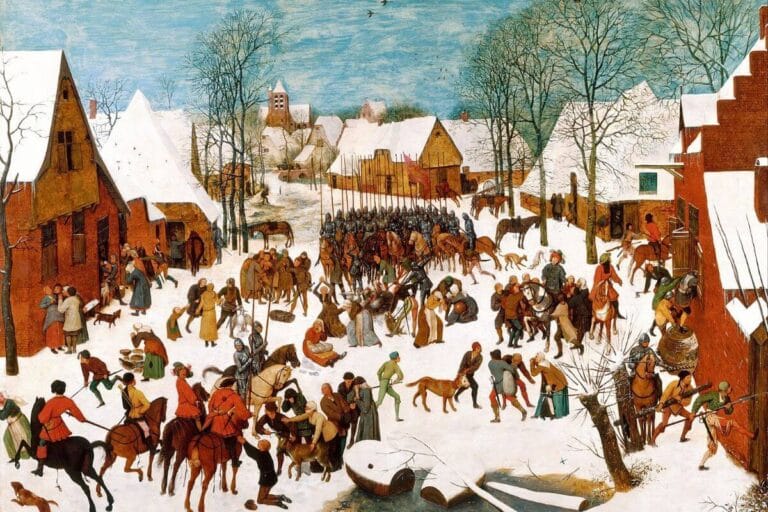

Renaissance Music is traditionally known as the period of classical music from around 1400 to 1600. The term ‘renaissance’ comes from the from the Latin renasci, meaning ‘to be reborn’. The Renaissance then was a period of rebirth, in which the arts and sciences of classical antiquity were revived, helped by the invention of the printing press. The emerging ideal of humanism, with a new emphasis on the human being, lead to a transition in the arts from a mystical, distant, and abstract approach in service of God to a more passionate, personal, and natural way of expression.

“[Humanism] stimulated practicing composers to experiment with ways to write music that better expressed the sentiments and emotions of the text. We could say that the whole history of vocal music in the Renaissance is the history of a continuous search for more expressive solutions. Earlier periods had not been always interested in the expression of text in music.”

Giulio Ongaro, Music of the Renaissance

The most important aspect of Renaissance Music was the development of complex polyphony, the use of four or more independent, interweaving melodic lines, both in vocal and instrumental music. It enabled composers to experiment with new ways of musical expression. Composers furthermore enjoyed a lot more freedom than those in the Middle Ages, because the church increasingly made way for the court as a musical centre. Renaissance Music is therefore defined by its sheer variety, with every region having a distinct, idiosyncratic style of music. In the section below, I will highlight three musical landscapes: the Franco-Flemish, Italy and Spain, and England.

Franco-Flemish School

(Wikimedia Commons)

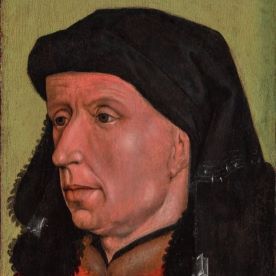

Johannes Ockeghem (c. 1410-1497) was the first great composer of the Franco-Flemish School, denoting Renaissance composers from France and the Burgundian Netherlands. Ockeghem began his career as a singer at the Antwerp Cathedral, but he later became the head of the royal chapel in France. He was praised for his mastery of the canon (i.e. exact imitation by different voices), his contrapuntal technique (i.e. composing melodic lines against another), and his compositional mastery of long and expressive melodic lines, which was a departure from the shorter phrasings of his predecessors, Dufay and Binchois. Besides some motets and chansons, Ockeghem is mostly known for his masses, especially his Missa prolationum and Missa de profunctis, the earliest surviving polyphonic requiem mass.

(Wikimedia Commons)

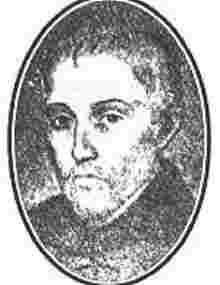

Josquin des Prez (c. 1450-1521) is generally considered the greatest composer of the Renaissance. Martin Luther said about Josquin that “he is the master of the notes and makes them do what he wants, whereas other composers must allow the notes do what they want.” Despite his fame, Josquin’s life is clouded in mystery. We do know that he spent most of his life in Italy, first as a singer at the Milan Cathedral and the papal choir and later as a composer and choirmaster at several courts in Italy and France, including the court of Ferrara.

Josquin might have been a pupil of Ockeghem, and he was certainly influenced by him before leaving Flanders, composing in a sober and reserved manner. In Italy, however, Josquin learnt to compose in a more fluent and flexible style, free of formulaic patterns, and using more expression in his music to convey the sentiments of the text. This use of ‘word-painting’ can be heard in his famous Nymphes des bois, a lament on the death of Johannes Ockeghem. When the text conveys feelings of grief, Josquin uses descending notes to underline this emotion. In the line ‘and let your eyes weep copious tears’ (et plorez grosses larmes d’oeuil), you can almost hear the teardrops fall down on the ground. But when paying his last respects to Ockeghem, commending him as ‘the true treasure and supreme master of music’ (vray trésoir de musique et chief d’oeuvre), Josquin lets the notes rise to a soaring height. Highlights from Josquin’s oeuvre are his mass Missa Pange lingua, the motets Ave Maria and Miserere, and the chansons Mille Regretz and Nymphes des bois.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Orlande de Lassus (c. 1532-1594) was a composer of the late Renaissance, belonging to the last generation of the Franco-Flemish School. Tradition says that as a child he was kidnapped no less than three times because of his beautiful singing voice. While this story is not undisputed, we do know that he left the Low Countries at the age of twelve in favour of Italy, where he would work as a singer. After becoming the maestro di cappella of the Saint John Lateran in Rome – a post that Palestrina would later assume –, Lassus eventually settled down in Munich, working at the court of the Duke of Bavaria.

In his music, Lassus combined the features of several national he had encountered, such as the Italian expressiveness, the French elegance, and the Flemish richness of sound. He was incredibly prolific, writing a lot of sacred and secular music. Besides his famous Psalmi Davidis poenitentiales, Lassus is mostly known for his countless secular songs, like the French chanson Suzanne un jour.

Italy and Spain

da Palestrina

(Wikimedia Commons)

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c. 1525-1594) is traditionally regarded as the pinnacle of late Renaissance polyphony. After serving as a chorister at the Santa Maria Magiore in Rome and as an organist at the San Agapito in his birthplace Palestrina, he attained the position of maestro di cappella at Saint Peter’s Basilica and later also at Saint John Lateran. It is said that the Bishop of Palestrina favoured the composed and, when he was elected as Pope Julius III, gave him a position at the vatican, where he remained for the rest of his life.

The position at the papal chapel gave him a steady income and allowed him to write countless works of music – both sacred and secular –, including masses, motets, magnificats, offertories, lamentations, madrigals, and a Stabat Mater. Palestrina had a conservative music outlook, which meant that he refined the existing styles rather than inventing new ones. His music is characterised by smooth harmonic progression and seamless textures, beautifully restrained yet expressive. Palestrina is best known for his Missa Papae Marcelli, a mass dedicated to Pope Marcellus II.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Tomás Luis de Victoria (c. 1548-1611) was the greatest Spanish composer of the Renaissance. Born in the city of Ávila, in central Spain, Victoria served as a chorister at the local cathedral. When his teachers saw that he was musically gifted, they sent him to their seminary in Rome. There, he would begin a successful career as an organist, choirmaster, and composer. Towards the end of his life, he returned to Spain to spend his remaining years in peace and quiet. Victoria wrote music in a style similar to that of Palestrina, but with a more dramatic and emotional expression. His most famous works are the motet O magnum mysterium, theTenebrae Responsories, and the Officium defunctorum.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Carlo Gesualdo (1566-1613) was the last major Italian Renaissance composer. Little is known about his early life, but we do know he was of noble birth, the son of a prince and related to Pope Pius IV. He was urged to pursue an ecclesiastical career, but when his brother died, Gesualdo had to assume the position of the next Prince of Venosa and married his cousin Maria d’Avalos. One day, however, Gesualdo caught his wife in flagrante delicto with her lover and he killed them both on the spot. While according to local custom he had the right and obligation to act as he did, the reputation of Gesualdo as a psychopath was born.

Gesualdo would later remarry and eventually became a prolific composer, but in his music you can still hear his suffering. Despite his act of cruelty, which has overshadowed his music ever since, Gesualdo composed heavenly vocal music, which can be characterised as expressive, chromatic, and highly original. He is best known for his madrigals and his Tenebrae Responsories.

England

(Wikimedia Commons)

Thomas Tallis (c. 1505-1585) was a composer from the English Renaissance. Little is known about his early years, but it is suggested that he served as an organist for the Catholic Priory in Dover, until Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries in 1540. A couple of years later, in 1543, Tallis would get a position at the Chapel Royal, where he remained the rest of his life. Thomas Tallis and his student William Byrd were so revered for their music, that Queen Elizabeth even gave them the monopoly for printing music in 1575.

Less interested in technical counterpoint, Tallis primarily wrote serene, chordal, and homophonic polyphony. Tallis was conservative in his musical outlook, as can be heard in his masses, motets, and keyboard music. However, his famous forty-part motet Spem in alium, which is considered to be a monument in English music history, shows his willingness to innovate and experiment.

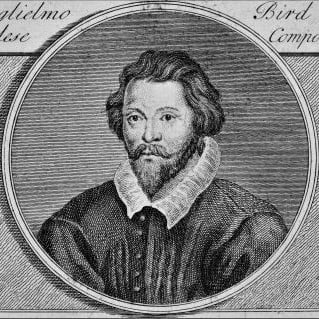

(Wikimedia Commons)

William Byrd (c. 1540-1623) was the greatest English composer of the Renaissance. Born in a wealthy and musical family in Londen, Byrd was a chorister in the Chapel Royal, where he became the pupil and close friend of Thomas Tallis. At the age of twenty, Byrd got a position as an organist at the Lincoln Cathedral, where he began to write sacred music. Queen Elizabeth later gave him a position at the Chapel Royal, which provided Byrd with a steady income and allowed him to spend most of his time composing.

When Queen Elizabeth gave Byrd and Tallis the monopoly for printing music in 1575, they published the Cantiones sacrae, a collection of motets, in the same year. From his friend and teacher Tallis, Byrd would adopt the intricate and flowing counterpoint. Having written masses, psalms, anthems, and keyboard music, Byrd would remain best known for his restrained yet expressive sacred works in Latin, such as the famous motet Ave verum corpus.

John Dowland

(Wikimedia Commons)

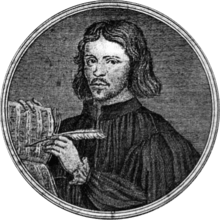

John Dowland (c. 1563-1626) was the most famous lutenist of the Renaissance. He served at several courts, including that of Christian IV of Denmark and James I of England. Still, he did not have an easy career: he was allegedly rejected by the court of Elizabeth I because he was a catholic, and despite his success he is said to have died in poverty. His personal moto was Semper Dowland, semper dolens (‘always Dowland, always doleful’), because his music was prone to melancholy. Dowland was most famous for his lute ayres, music for voice and lute. He was certainly at his best when writing somber and melancholic music, such as the intensely passionate and mournful lament In darkness let me dwell.

In darkness let me dwell; the ground shall sorrow be,

The roof despair, to bar all cheerful light from me;

The walls of marble black, that moist’ned still shall weep;

My music, hellish jarring sounds, to banish friendly sleep.

Thus, wedded to my woes, and bedded in my tomb,

O let me living die, till death doth come, till death doth come.

Overview of Renaissance Composers

(Wikimedia Commons)

- Franco-Flemish School

- Guillaume Dufay

- Johannes Ockeghem

- Jacob Obrecht

- Josquin des Prez

- Heinrich Isaac

- Orlande de Lassus

- Italy and Spain

- Cristóbal de Morales

- Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

- Francisco Guerrero

- Tomás Luis de Victoria

- Alonso Lobo

- Carlo Gesualdo

- England

- John Taverner

- Cristopher Tye

- Thomas Tallis

- John Sheppard

- William Byrd

- John Dowland